General view of French WWI soldier Edouard Marius Ivaldi's battlefield grave memorial, a wooden cross with a battlefield helmet in Champagne, eastern France, November 3, 2015. The plaque which reads in part, "In Memory of Edouard Marius Ivaldi, Corporal in the 7th Infantry Regiment. Died for France on April 30, 1917", was placed there by Ivaldi's father in 1919. World War One historians estimate that on the western front half of the fallen soldiers were never found or identified. Edouard Marius Ivaldi is one of these. After the war, his father Jean-Joseph searched for the remains of his son and started the grieving process. In 1919 he placed a wood cross on the spot where his son fell in combat, then in 1924 he placed a plaque with his son's name in the chapel of the Navarin Ossuary. Almost 100 years later, this place of private memory, its location unknown to visitors, has remained untouched over time. (Photo by Charles Platiau/Reuters)

WWI shell craters and trenches are seen near French WWI soldier Edouard Marius Ivaldi's battlefield grave memorial, in Champagne, eastern France, November 3, 2015. (Photo by Charles Platiau/Reuters)

A rusty French flask hangs on a tree to indicate the way to the battlefield grave memorial of French WWI soldier Edouard Marius Ivaldi in Champagne, eastern France, November 3, 2015. (Photo by Charles Platiau/Reuters)

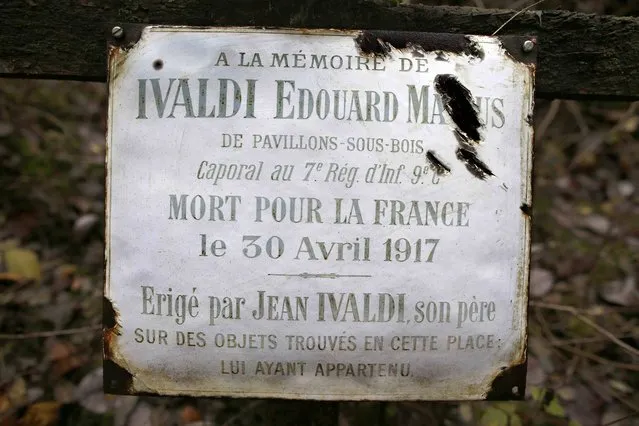

A plaque hangs over the cross of the battlefield grave memorial of World War I French soldier Edouard Marius Ivaldi in Champagne, eastern France, November 3, 2015. The plaque which reads in part, "In Memory of Edouard Marius Ivaldi, Corporal in the 7th Infantry Regiment. Died for France on April 30, 1917", was placed there by Ivaldi's father in 1919. World War One historians estimate that on the western front half of the fallen soldiers were never found or identified. (Photo by Charles Platiau/Reuters)

A portrait of French WWI soldier Edouard Marius Ivaldi is displayed on a tablet, in this illustration picture, alongside his battlefield grave memorial, a wooden cross with a battlefield helmet in Champagne, eastern France, November 3, 2015. (Photo by Charles Platiau/Reuters)

The rusty French army helmet on top a wooden cross is seen on French WWI soldier Edouard Marius Ivaldi's battlefield grave memorial, in Champagne, eastern France, November 3, 2015. (Photo by Charles Platiau/Reuters)

French WWI soldier Edouard Marius Ivaldi (Top centre) poses with fellow soldiers in this 1917 picture. The soldier died for France on April 30, 1917. World War One historians estimate that on the western front half of the fallen soldiers were never found or identified. (Photo by Charles Platiau/Reuters)

A plaque which reads 'Happy Saint Name Day' hangs over a battlefield grave memorial of French WWI soldier Edouard Marius Ivaldi in Champagne, eastern France, November 3, 2015. The soldier died for France on April 30, 1917. (Photo by Charles Platiau/Reuters)

General view of the Navarin monument, a pyramid inaugurated at Sommepy-Tahure in 1924 to pay tribute to World War I soldiers killed in Champagne, eastern France, November 3, 2015. The ossuary is the shelter of more than 10,000 unidentified corpses of soldiers. Inside there is a chapel which walls are covered with plates placed by the families in memory of the dead soldiers, among them a plate placed there by Ivaldi's father, Jean-Joseph in honour of his son. The soldier died for France on April 30, 1917. (Photo by Charles Platiau/Reuters)

WWI barbed wire is seen near the Navarin monument, a pyramid inaugurated at Sommepy-Tahure in 1924 to pay tribute to World War I soldiers killed in Champagne, eastern France, November 3, 2015. (Photo by Charles Platiau/Reuters)

A warning road sign is posted near the entrance of the Camp de Suippes, near Reims, France, November 3, 2015. During World War One many French villages were destroyed, some never to be reconstructed because they were heavily damaged or because the nearby fields contain unexploded munitions, mines, explosives and artillery shells. The Camp de Suippes, opened in 1922, is a French Army training area for live artillery firing exercises, and closed to the public. The camp includes five damaged villages, with their churches and cemeteries that are overgrown with vegetation. The sign reads "Permanent live firing area, Danger of Death, Prohibited zone". (Photo by Charles Platiau/Reuters)

A "Borne du front" (Demarcation stone) with a helmet capping the milestone is seen near the entrance of Camp de Suippes, near Reims, France, November 3, 2015. A total of 118 markers were erected (22 in Belgium, 96 in France) in the years between 1921-1927 by French sculptor Paul Moreau-Vauthier to create a line of small monuments to be located along the line on the Western Front which was the furthest point to which the German Army had penetrated into France. The milestone reads "Here in 1918 at Souan the invader was pushed back". (Photo by Charles Platiau/Reuters)

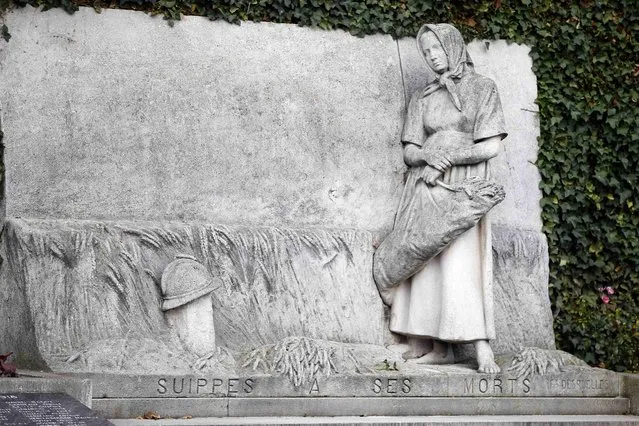

General view of the Suippes war memorial, near Reims, France, November 3, 2015. Sculpted by Felix Desruelles and inaugurated in 1930, it shows a young farmer paying tribute to a French soldier's grave on a battlefield which turns into a grain field. The Camp de Suippes, opened in 1922, is a French Army training area for live artillery firing exercises, and closed to the public. The camp includes five damaged villages, with their churches and cemeteries that are overgrown with vegetation. (Photo by Charles Platiau/Reuters)

WWI shell craters and trenches are seen at the Beausejour farm's site, the scene of bloody actions of the Champagne front, inside the Camp de Suippes, near Reims, France, November 3, 2015. (Photo by Charles Platiau/Reuters)

General view of church ruins at Mesnil les Hurlus, a former village of 97 people now included in the Camp de Suippes, near Reims, France, November 3, 2015. (Photo by Charles Platiau/Reuters)

General view of cemetery ruins at Mesnil les Hurlus, a former village of 97 people now included in the Camp de Suippes, near Reims, France, November 3, 2015. Badly damaged headstones from the pre-war cemetery stand nearby the church. (Photo by Charles Platiau/Reuters)

General view of church ruins and the altar at Perthes-les-Hurlus, a former village of 151 inhabitants in 1914, seen November 3, 2015. The village is now largely covered by woodland and is located inside the Camp de Suippes, near Reims, France. Badly damaged headstones from the pre-war cemetery stand nearby the church. (Photo by Charles Platiau/Reuters)

The ruins of the 13th century church of St. Remi at Hurlus, sit atop a small mound, near Reims, France, November 3, 2015. Part of the sanctuary is still standing and three of the five windows are intact, but most the rest of the building has been reduced to rubble. Hurlus, a village with 88 inhabitants in 1911, is located inside the Camp de Suippes. (Photo by Charles Platiau/Reuters)

General view of the ruins of the church at Tahure, near Reims, France, November 3, 2015. Tahure consisted of 185 people in 1914. The church and much of the village sit on a small hill - the Butte de Tahure - another place which became famous during the Great War. The wall foundations of the church were rediscovered in 1980, and these have now been excavated. Remarkably the original altar was found, and the bas-relief on its face is largely intact. Tahure is located inside the Camp de Suippes. (Photo by Charles Platiau/Reuters)

A sculpture representing three World War I soldiers in an attack position is seen on top of the Navarin monument, a pyramid inaugurated at Sommepy-Tahure in 1924 to pay tribute to World War I soldiers killed in Champagne, eastern France, November 3, 2015. From R to L; Quentin Roosevelt, son of former American President, the General Gouraud, head of the IVth army and the sculptor's brother who died at the Moulin of Laffaux. (Photo by Charles Platiau/Reuters)

The ruins of the 13th century church of St. Remi at Hurlus, sit atop a small mound, near Reims, France, November 3, 2015. (Photo by Charles Platiau/Reuters)

Various items are gathered in the ruins of the church at Perthes-les-Hurlus, a former village of 151 inhabitants in 1914, on the Champagne front near Reims, November 3, 2015. The village is largely covered by woodland now and is located inside the Camp de Suippes. Badly damaged headstones from the pre-war cemetery stand nearby the church. (Photo by Charles Platiau/Reuters)

General view of church ruins and the altar at Perthes-les-Hurlus, a former village of 151 inhabitants in 1914, seen November 3, 2015. (Photo by Charles Platiau/Reuters)

A sculpture representing three World War I soldiers in an attack position is seen on top of the Navarin monument, a pyramid inaugurated at Sommepy-Tahure in 1924 to pay tribute to World War I soldiers killed in Champagne, eastern France, November 3, 2015. (Photo by Charles Platiau/Reuters)

General view of church ruins and the altar at Perthes-les-Hurlus, a former village of 151 inhabitants in 1914, seen November 3, 2015. The village is now largely covered by woodland and is located inside the Camp de Suippes, near Reims, France. (Photo by Charles Platiau/Reuters)

09 Nov 2015 08:02:00,

post received

0 comments