Tashi Phutit, 81, a wheat farmer and housewife poses for a photograph in the village of Stok, 15 km from Leh, the largest town in the region of Ladakh, nestled high in the Indian Himalayas, India September 27, 2016. When asked how living in the world's fastest growing major economy had affected her life, Phutit replied: “Now we can eat better types of vegetables and we can wear better types of clothes. The problem is people are becoming greedy”. world's fastest-growing major economy that are eroding their age-old Buddhist culture but opening up new opportunities. People have long wrested a living from herding goats and tending wheat fields ringed by 6,000-m (19,685-ft) snow-capped peaks, while Buddhist monasteries dotting the landscape are a reminder of the region's ties to its eastern neighbour, Tibet. Traditions are fading fast as larger numbers of India's burgeoning middle class flock to holiday in the tranquillity of the lunar-like terrain. (Photo by Cathal McNaughton/Reuters)

Travel agent, Stanton Othsil, 29, sits in the sun in Leh, the largest town in the region of Ladakh, nestled high in the Indian Himalayas, India September 29, 2016. When asked how living in the world's fastest growing major economy had affected life, Othsil said: “More tourists are coming now, especially Indians who are spending more money”. (Photo by Cathal McNaughton/Reuters)

Tsewang Lhadon, 36, a housewife, poses for a photograph in Choklamsar, a village nestled high in the Indian Himalayas, India September 27, 2016. When asked how living in the world's fastest growing major economy had affected life, she replied, “The children get a better education and are eating more nutritious food because of the government subsidies”. (Photo by Cathal McNaughton/Reuters)

Tsering Dolma, 51, a housewife and farmer poses for a photograph in Matho, a village nestled high in the Indian Himalayas, India September 29, 2016. When asked how living in the world's fastest growing major economy had affected life, Dolma replied: “We can now afford new machinery due to subsidies which makes our job much easier”. (Photo by Cathal McNaughton/Reuters)

Tsewang Dolma, 33, a farmer and housewife poses for a photograph in Matho, a village nestled high in the Indian Himalayas, India September 29, 2016. When asked how living in the world's fastest growing major economy had affected life, Dolma replied: “Our culture is spoiled now. We don't wear our traditional dress”. (Photo by Cathal McNaughton/Reuters)

Dorsey Takapa, 65, a retired goat herder poses for a photograph in Choklamsar, a village nestled high in the Indian Himalayas, India September 27, 2016. When asked how living in the worlds fastest growing major economy had affected life, Takapa replied: “Traditional values are being lost as we focus on money”. (Photo by Cathal McNaughton/Reuters)

Phunchok Angmo, 33, a mathematics teacher, poses for a photograph at Thiksey monastery, near Leh, the largest town in the region of Ladakh, nestled high in the Indian Himalayas, India September 28, 2016. When asked how living in the world's fastest growing major economy had affected life, Angmo replied: “The children here no longer care about the culture and they spend less time talking to each other. They spend their free time on laptops”. (Photo by Cathal McNaughton/Reuters)

Testing Yangchan, 60, a housewife, poses for a photograph in Choklamsar, a village nestled high in the Indian Himalayas, India September 27, 2016. When asked how living in the world's fastest growing major economy had affected life, Yangchan replied: “Medical facilities are much better although crime has risen”. (Photo by Cathal McNaughton/Reuters)

Lights from shops illuminate the city of Leh, the largest town in the region of Ladakh, nestled high in the Indian Himalayas, India September 26, 2016. (Photo by Cathal McNaughton/Reuters)

Testing Yangchan, 60, a housewife, poses for a photograph in Choklamsar, a village nestled high in the Indian Himalayas, India September 27, 2016. (Photo by Cathal McNaughton/Reuters)

Prayer flags stretch towards Tsemo Monastery in the city of Leh, the largest town in the region of Ladakh, nestled high in the Indian Himalayas, India September 26, 2016. (Photo by Cathal McNaughton/Reuters)

A man walks past shops as the sun sets in Leh, the largest town in the region of Ladakh, nestled high in the Indian Himalayas, India September 29, 2016. (Photo by Cathal McNaughton/Reuters)

Phunchok Angmo, 33, a mathematics teacher, poses for a photograph at Thiksey monastery, near Leh, the largest town in the region of Ladakh, nestled high in the Indian Himalayas, India September 28, 2016. (Photo by Cathal McNaughton/Reuters)

The sun sets in Leh, the largest town in the region of Ladakh, nestled high in the Indian Himalayas, India September 26, 2016. (Photo by Cathal McNaughton/Reuters)

Stakna monastery catches the evening light near Leh, the largest town in the region of Ladakh, nestled high in the Indian Himalayas, India September 27, 2016. (Photo by Cathal McNaughton/Reuters)

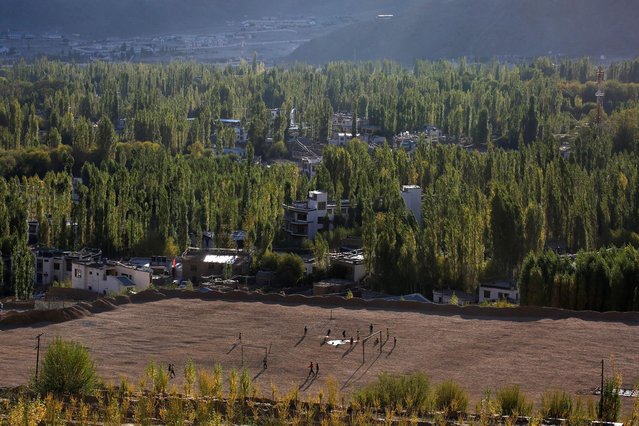

People play polo in Leh, the largest town in the region of Ladakh, nestled high in the Indian Himalayas, India September 24, 2016. (Photo by Cathal McNaughton/Reuters)

Children look down from the Royal Palace in Leh, the largest town in the region of Ladakh, nestled high in the Indian Himalayas, India September 26, 2016. (Photo by Cathal McNaughton/Reuters)

Children play on a school playground as the sun sets in Leh, the largest town in the region of Ladakh, nestled high in the Indian Himalayas, India September 24, 2016. (Photo by Cathal McNaughton/Reuters)

Vegetable vendors chat in Leh, the largest town in the region of Ladakh, nestled high in the Indian Himalayas, India September 29, 2016. (Photo by Cathal McNaughton/Reuters)

13 Oct 2016 11:32:00,

post received

0 comments