The phrase “epic journey” gets used a lot, but it’s usually an exaggeration. This time it’s an understatement. Earlier this year Paul Salopek (seen here in Ethiopia’s Afar desert) embarked on a seven-year global trek, walking from Africa to Tierra del Fuego in the footsteps of our ancestors. Why? “For many reasons”, he writes in the December issue of National Geographic. “To relearn the contours of our planet at the human pace of three miles an hour. To slow down. To think. To write. To render current events as a form of pilgrimage. I hope to repair certain important connections burned through by artificial speed, by inattentiveness. I walk, as everyone does, to see what lies ahead. I walk to remember”. (Photo by John Stanmeyer/National Geographic)

“This is the critical moment when everything goes right or everything goes wrong”, said extreme kayaker Tyler Brandt, describing this shot of him – an online Extreme Photo of the Week – going over the 65-foot Tomata 1 waterfall in Tlapacoyan, Mexico. It’s important for waterfall kayakers to land precisely, an outcome influenced by their actions at the lip of the waterfall and into the first 20 feet of free fall. “At this moment”, explained Brandt, “I was focused on setting my angle correctly”. (Photo by Tim Kemple/National Geographic)

Mankind has always dreamed of flying. For some brave souls today, BASE jumping – where people leap from fixed objects (“BASE” is an acronym for “building, antenna, span, cliff”) and use a parachute to control their fall – comes pretty close. This shot, taken in Italy by Stela Prodanovic, was published in the Your Shot “Travelogue” story. (Photo by Stela Prodanovic/National Geographic)

The fathers of flight are the Wright brothers, right? Maybe not. As National Geographic Daily News reported in May, some aviation historians now believe a German-born inventor named Gustave Whitehead – seen here with his daughter Rose – beat the brothers into the air by as much as three years. Though many experts disagree or remain dubious, an Australian flight historian named John Brown has convinced the aviation bible Jane’s All the World’s Aircraft that an enhanced photograph shows Whitehead flying his plane in Fairfield, Connecticut, on August 14, 1901. Which way this piece of history tilts remains up in the air. (Photograph by Corbis/National Geographic)

Where would we be without failure? Hannah Bloch takes up this existential question in the September issue of National Geographic, examining the necessary flip side of success. “Failure”, writes Bloch, “is the specter that hovers over every attempt at exploration. Yet without the sting of failure to spur us to reassess and rethink, progress would be impossible”. Famous failures abound, including that of explorer Robert Peary, seen here in 1909 peering over Arctic ice on his third try to reach the North Pole. “Even at their most miserable,” writes Bloch, “failures provide information to help us do things differently next time”. (Photo by Robert E. Peary/National Geographic)

Looming above the landscape in northeastern Wyoming sits the Devils Tower. This monolith came from the bowels of the earth as magma, cooling into vertical columns, most of which are six-sided. Popular with climbers, the Tower is also an important figure in many American Indian traditions, including the Cheyenne, Crow, and Arapaho. (Photo by Aaron Huey/National Geographic)

The Maya civilization has long fascinated those curious about the past, as well as the future. In the August edition of National Geographic, we explored underwater wells – called cenotes – to understand how the Maya used the water, the position of the sun, and a series of shadows to influence their architecture and craft their highly regarded calendar. (Photo by Paul Nicklen/National Geographic)

To celebrate the 125th anniversary of the National Geographic Society, the October issue of National Geographic focused on discoveries through photography. This portrait shows footprints in volcanic ash at Engare Sero in Tanzania – believed to belong to a fast-moving party of adults and adolescents in the Pleistocene era, more than 10,000 years ago. The footprints provide evidence of modern humans moving through East Africa. (Photo by Robert Clark/National Geographic)

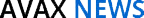

For decades Afghanistan has been at the crossroads of culture and conflict, leaving the country strewn with a plethora of buried artifacts. By one estimate, more than 99 percent of Afghanistan’s archaeological sites have been looted, items stolen by farmers enriched by the high value of rare antiquities. National Geographic Daily News went digging with several looters to get an inside look at the country’s historic artifacts and how people avoid arrest for breaking the law. (Photo by John Wendle/National Geographic)

In June, archeologists uncovered the first unlooted royal tomb from the Wari civilization. The ancient people are often overshadowed by their historic successors, the Inca, but the Wari built South America’s earliest empire in modern-day Peru between 700 and 1000. The high quality of Wari artwork has long attracted international attention, to the point that a pair of wooden ear ornaments with global frontal discs were a big hit for archeologists – and readers of National Geographic Daily News. (Photo by Robert Clark/National Geographic)

Each week, National Geographic Daily News publishes a handful of the best space photos, many taken from orbiting satellites and others from the ground pointing up. Here, Native American art was shot against the vibrant Milky Way. (Photo by Tony Rowell/National Geographic)

Eurasian otters are enjoying a fragile revival in the British Isles. For decades industrial pollutants – insecticides, fungicides, organochlorides, and DDT – leached into rivers there, and by the late 1970s the British otter population had all but collapsed. The mammals also went extinct in the Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg, and in most of France, Germany, and Italy as well. But as chemical bans slowly took effect, writes Adam Nicolson in the February issue of National Geographic magazine, “the population started to climb back toward health”. By 2010 nearly 60 percent of English riverbanks were occupied by otters. Today “only the London area and some northern industrial cities remain otter-free”. (Photo by Charlie Hamilton James/National Geographic)

Cave paintings from ancient humans have been discovered all over the world. The artists behind them, it turns out, were primarily women – says a study uncovered in April and reported on National Geographic Daily News. How did researchers know? Along with images of game animals, handprints on cave walls were analyzed for their anatomical sizes. On male hands, the ring finger is generally longer than the index finger. On female hands – like many of the ones found on cave walls – the lengths were reversed. (Photo by Dean Snow/National Geographic)

“Cassowaries are large, flightless birds related to emus and (more distantly) to ostriches, rheas, and kiwis”, writes Olivia Judson in the September issue of National Geographic magazine. How large? People-size: Adult males stand well over five foot five and top 110 pounds. Females are even taller, and can weigh more than 160 pounds. Dangerous when roused, they’re shy and peaceable when left alone. But even birds this big and tough are prey to habitat loss. The dense New Guinea and Australia rain forests where they live have dwindled. Today cassowaries might number 1,500 to 2,000. And because they help shape those same forests – by moving seeds from one place to another – “if they vanish”, Judson writes, “the structure of the forest would gradually change” too. (Photo by Christian Ziegler/National Geographic)

Russia’s Wrangel Island couldn’t be colder or more remote – a nature reserve on the 180th meridian that requires government permits to visit and a helicopter or icebreaker to reach. But that splendid isolation, writes Hampton Sides in the May issue of National Geographic magazine, “has led to an astonishing abundance of life”, past and present. Paleontologists say it’s the last place where woolly mammoths lived. Today it’s home to snowy owls, muskoxen, arctic foxes (like this pup playing with a lemming carcass), reindeers, and the largest population of Pacific walruses. It also serves as the world’s biggest denning ground for polar bears. This photo gallery of its current residents merely flicks at the island’s biodiversity. (Photo by Sergey Gorshkov/National Geographic)

“Thirty years ago the yacare caiman appeared to be heading for oblivion”, writes Roff Smith in the July issue of National Geographic magazine, “ruthlessly hunted to supply a lucrative market for crocodilian leather. Their numbers dropped alarmingly”. But “a Brazilian government crackdown on poaching and a 1992 global ban on the trade of wild crocodilian skins eased the pressure on the beleaguered yacare population. The crocs themselves did the rest. After a string of intense rainy seasons – ideal for breeding – caiman numbers rebounded dramatically. As many as ten million yacare caimans are estimated to live in the wetlands today”. (Photo by Luciano Candisani/National Geographic)

What’s in a name? Puma, panther, painter, brown tiger, catamount, mountain screamer, mountain lion – the cougar answers to all of them. And with a range that extends from Chile to the edge of Canada’s Yukon, writes Douglas Chadwick, it’s the most widespread large, land-dwelling mammal in the Western Hemisphere. Yet cougars are among the least seen and most elusive. For a better look at this controversial, poorly understood cat, see what photographer Steve Winter’s camera – and camera traps – turned up in the December issue of National Geographic magazine. (Photo by Steve Winter/National Geographic)

In March a team of scientists and filmmakers explored a remote Australian peninsula – a “lost world” that’s been cut off for millennia. They found three new species there, including a leaf-tailed gecko. Funded by the National Geographic Expeditions Council, the Cape York Biodiversity Expedition was led by Harvard University researcher and National Geographic photographer Tim Laman. “What’s really exciting about this expedition”, Laman told National Geographic Daily News, “is that in a place like Australia, which people think is fairly well explored, there are still places like Cape Melville where there are all these species to discover. There’s still a big world out there to explore”. (Photo by Tim Laman/National Geographic)

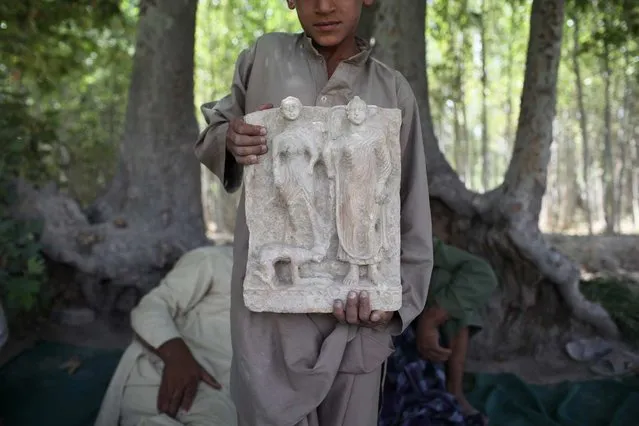

Katydids (pictured) are oblong-winged insects. Most of them are green, but a few have been found sporting bright colors: yellow, orange, even hot pink. Geneticists aren’t sure why. Entomologists suspect erythrism, an anomaly similar to albinism. Scientists working with a related species in Japan point to genetics over environmental factors. Meantime, recent mating trials in New Orleans have posited green as a recessive trait – good camouflage just makes them fittest for survival. Meaning it’s easier being green. (Photo by Joel Sartore/National Geographic)

In a Finnish boreal forest near the Russian border, a brown bear cub rests against a tree after a long evening of playing with other young bears. This playful picture, taken by Erik Mandre, was a Your Shot hit twice over: National Geographic’s photo editors chose it in March for the online Daily Dozen, then published it again in October in the magazine. (Photo by Erik Mandre/National Geographic)

“Every year”, writes Jonathan Franzen in the July issue of National Geographic magazine, “from one end of it to the other, hundreds of millions of songbirds and larger migrants are killed for food, profit, sport, and general amusement. The killing is substantially indiscriminate, with heavy impact on species already battered by destruction or fragmentation of their breeding habitat. Mediterraneans shoot cranes, storks, and large raptors for which governments to the north have multimillion-euro conservation projects. All across Europe bird populations are in steep decline, and the slaughter in the Mediterranean is one of the causes”. Franzen’s eye-opening article is accompanied by David Guttenfelder’s affecting photographs. In this one, a songbird rescuer in Cyprus uses his saliva to remove sticky plum tree sap from a blackcap’s feather and feet, so that the bird can safely fly when released. (Photo by David Guttenfelder/National Geographic)

In honor of our 125th anniversary, we’re sharing National Geographic photographs – many never before published – that reveal cultures and moments of the past. In this one, taken in 1967 by the famed photographer William Albert Allard, American bison charge through heavy snow in Yellowstone National Park. (Photo by William Albert Allard/National Geographic)

What face does America show the world? The answer used to be more black and white. But today more and more people are of mixed heritage. In the 2000 census, when a multiple-race option appeared for the first time, 6.8 million Americans checked it off. Ten years later that number grew by 32 percent. The quickly changing fabric of our country – where familiar racial categories are being joined by new ones rooted in self-determined identity – provides an opportunity to re-examine our definitions and assumptions. It’s also a chance to gaze at a gallery of intriguing faces and features, photographed by Martin Schoeller. (Photo by Martin Schoeller/National Geographic)

Libya has been a recent flashpoint of global conflict and foreign policy debate. In 2011 civil war engulfed the North African country, prompting a NATO-led military intervention that ended Muammar Qaddafi’s life and long dictatorship. In 2013, Robert Draper’s February cover story in National Geographic magazine looked at how Qaddafi’s “warped vision” and “tangled philosophy” twisted Libya’s connection to its own rich history, neglecting cultural and archaeological treasures from Cyrene in the east to Sabratah in the west. Yet the story also looked forward, optimistically, to a post-conflict country and the challenge its citizens face in forging a new identity (re)attached to their past. (Photo by George Steinmetz/National Geographic)

06 Jan 2014 12:21:00,

post received

0 comments