In South Korea plastic surgery is everywhere, geared toward everyone. Even pre–high school students feel pressure to physically alter themselves in pursuit of a fantasy ideal. Photographer and artist Ji Yeo’s Beauty Recovery Room project visualizes this disturbing cultural trend in an October post from PROOF. Yeo describes her series as using “the wounded faces and bodies of women who have recently undergone plastic surgery to show the physical cost of social pressure in Korea. Going under the knife, enduring bruises, scars, and being under general anesthetic several times are no longer considered risky or extravagant. They have all had multiple procedures and have plans for future augmentation”. (Photo by Ji Yeo/National Geographic)

Beneath Europe’s modern veneer is a primal connection to nature. From the beginning of December till Easter, festivals across the continent celebrate harvests and solstices, rites of passage and superstitions. Though most are tied to Christian holidays, many feature pre-Christian rituals – a “tribal Europe” where men cavort in costumes that blur the lines separating human and animal, civilization and wilderness, death and rebirth. A gallery of Charles Fréger’s photographs, from a story in the April National Geographic, show how these wild men, in full regalia, represent the complicated relationship human communities still have with nature. (Photo by Charles Fréger/National Geographic)

This close-up image – of a Holi Festival celebrant in Vrindivan, India, coated in neon-colored powder – was submitted to National Geographic’s Your Shot in the last week of March. On April 1 we published it on our Daily News site, along with seven other bright scenes captured during the Hindu spring Festival of Colors. (Photo by Tinto Alencherry/National Geographic)

Ecuador’s Yasuní National Park is one of the wildest places in the world. Sitting at the intersection of the Andes, the Equator, and the Amazon region, it’s home to countless plant and animal species, and to two indigenous nations. It also harbors a buried treasure: hundreds of millions of barrels of untapped Amazon crude. Now demand for that oil is imperiling life in the park. A feature story in the January issue of National Geographic magazine – written by Scott Wallace, photographed by Steve Winter – asks: What will happen if economic interests ultimately trump conservation? (Photo by Steve Winter/National Geographic)

Hydraulic fracturing, aka fracking, is a controversial method of extracting oil from the ground. It offers new opportunities for domestic gas and oil production, but its environmental implications are unclear – and alarming. With a national debate raging over fossil-fuel consumption and renewable-energy strategies, National Geographic’s March cover story examines the potential risks and rewards of fracking in North Dakota. (Photo by Eugene Richards/National Geographic)

Nitrogen fertilizer has shaped our planet. The crops we depend on for survival – corn, wheat, and rice – are grown using a hundred million tons of the stuff each year. But its toll on water, air, and wildlife is steep. As Dan Charles writes in the May issue of National Geographic, “runaway nitrogen is suffocating lakes and estuaries, contaminating groundwater, and even warming the globe’s climate. As a hungry world looks ahead to billions more mouths needing nitrogen-rich protein, how much clean water and air will survive our demand for fertile fields?” (Photo by Peter Essick/National Geographic)

These fishermen in Taiwan are the last practitioners of an old technique. Working in the waters near New Taipei City, they go out in a boat and light acetylene torches – then watch as the sulfuric fire draws mackerel into their nets. This image was published in September’s Visions of Earth, a trio of photos that appear in each issue of National Geographic magazine. (Photo by Chang Ming Chih/National Geographic)

This photograph – an underwater shot of tadpoles swimming through a jungle of lily stalks in Cedar Lake on Vancouver Island, Canada – was our online Photo on January 2. Our editors liked Eiko Jones’s picture so much they published it again, this time in the April issue of National Geographic magazine. (Photo by Eiko Jones/National Geographic)

A man on the Belt Parkway seawall near Brooklyn’s Fort Hamilton braces for impact as a wall of water looms above him in this picture taken in October 1948. Published as a Flashback in the September issue of National Geographic magazine, parts of the area were inundated again when Hurricane Sandy roared ashore in October 2012. (Photo by New York Daily News/National Geographic)

The laptops, cameras, gaming systems, and other electronic gear that consumers eagerly buy often come with a hidden, painful cost. Many of these items, as well as pieces of high-price jewelry, contain minerals – gold, diamonds, tin, copper, and tantalum, among others – that have been illegally dug out from mines in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Government officials, soldiers, and militia warlords fight over the spoils, killing thousands of people each year, most of them civilians. In the October issue of National Geographic, writer Jeffrey Gettleman and photographer Ed Kashi reported on the bloody business of conflict minerals – and on whether a budding campaign to stop companies from using ill-gotten resources will make a difference. (Photo by Marcus Bleasdale/National Geographic)

Fifty years ago 200 fishing boats went out every summer into Norway’s coastal waters to harpoon whales for meat, bringing wealth to the small villages in the Lofoton Islands above the Arctic Circle. Today only 20 whaleboats go out on the hunt, as the children and grandchildren of whalers leave the remote communities to seek new pursuits. A June feature in National Geographic reports on the demise of the traditional whaling industry and the approaching end to a hardy way of life. (Photo by Marcus Bleasdale/National Geographic)

Humans and lions have almost every reason to stay clear of one another; each is too dangerous to the other. But even as the number of lions continues to decline rapidly in Africa, their interactions with people have increased as farms, hunting preserves, and other development encroach on wilderness. Brett Stirton’s images for an August feature in National Geographic reveal how both lions and humans suffer when home territories collide. (Photo by Brent Stirton/Getty Images/National Geographic)

North Korea is the most secretive, walled-off nation in the world. Its totalitarian regime demands total obedience. Its citizens cannot travel or speak to foreigners without permission. Propaganda clouds what is real and what is not. In July’s eye-opening story in National Geographic, writer Tim Sullivan and photographer David Guttenfelder used their access as journalists for the Associated Press to move around the country and peer beyond the facade. “We’ve traveled to collective farms, attended countless political rallies, and visited Pyongyang hot spots like the Gold Lane bowling alley”, writes Sullivan, “where the capital’s elite hoist battered balls made in America”. (Photo by David Guttenfelder/AP Photo/National Geographic)

A man to reckon with, a painted tribesman from southern Ethiopian guards his village with an AK-47 cradled in his arms. The imposing stance, the confident expression, and the way light highlights his face made this photograph by Benjamin Eagle for Your Shot an editor’s choice in February for “Pictures We Love”. (Photo by Benjamin Eagle/National Geographic)

One of the most urgent conservation issues of the day is how to slow the booming illegal trade in African ivory. Crime syndicates continue to slaughter African elephants by the tens of thousands each year and smuggle the tusks into Asia, where the ivory is carved into everything from chopsticks to religious figurines. As part of its ongoing coverage of the ivory crisis, National Geographic Daily News reported in June on how the Philippines became the first Asian country to destroy its seized ivory to keep it off the black market. (Photo by Brent Stirton/National Geographic)

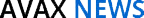

Luxury and adversity mingle in this dichotomous image made by Pascal Maitre. The opulent ensembles these men style look out of place in the littered streets of Kinshasa. For Les Sapeurs, members of the Société des Ambianceurs et des Personnes Elégantes (the Society of Tastemakers and Elegant People), their clothes are as much about extravagance as they are about creativity. But beyond being a form of self-expression, it is a lifestyle about poise and propriety. Good manners, attention to detail, visual perfection, and social etiquette are of utmost importance to these gentlemen. Although often spending exorbitant amounts of money on clothes in a country where nearly half the population lives beneath the national poverty line, like all of us, they are striving to carve out their identities in the world, moving beyond class and circumstance. (Photo by Pascal Maitre/National Geographic)

David Whitmore, Design Director: “I can see Edward Steichen’s pond in moonlight and Maurice Sendak’s enchanted bedroom of wild things in this nocturnal scene. Smudged umbers and coal-black embers contrast against cool gray green grass dissolving into lavender sky. The Dreamtime. The time of ancients, alive in that space, not quite night, not quite day. With this image, Amy Toensing captures what she set out to find in this story: a spirit presence in the land and our closer understanding of the Aboriginals’ sustained state of awakening to that spirit”. (Photo by Amy Toensing/National Geographic)

Elizabeth Grady, Rights Manager: “After glancing through the entire year, this image drew me in the most for some reason. I love the innocence, the ephemeral quality, the movement, the sweetness”. (Photo by Marcus Bleasdale/National Geographic)

Ken Geiger, Deputy Director of Photography: “One of the most amazing stories I’ve seen in the short time I’ve worked here is Nick Nichols’s photo coverage of “The Short Happy Life of a Serengeti Lion”, which ran in the August 2013 issue. Not only is this image hauntingly beautiful, as are many images in the story, but what makes this image gripping is the moment created by the intensity of the lion’s eyes combined with the intimacy of having the camera on the same level as the lion. Those two factors create such a gripping image that I’ve never tired of seeing it. I also have such an amazing respect for this set of images – they reset the bar for all brilliant wildlife photography. Nick, along with the gift of time on the ground, used and cobbled numerous pieces of technology so that he could capture never before seen images of lions. That kind of dedication to the craft of photography – and using every tool available to tell a story that moves the dial on lion conservation – is a pleasure to behold”. (Photo by Michael Nichols/National Geographic)

Sadie Quarrier, Senior Photo Editor: “One of the most memorable stories I worked on this year was Yasuní National Park (“Rain Forest for Sale”). It was a special story because we conducted a photo blitz, sending five photographers for one month to document every aspect of this Ecuadorian park, from threatened species and isolated tribes to oil drilling and deforestation. They delivered a wealth of visual riches. Photographers Ivan Kashinsky and Karla Gachet worked together to cover the Waorani people, immersing themselves in the daily lives of the tribe and documenting the impact oil companies have had on their culture. This image of Waorani hunters by Ivan stays with me. I love its rawness – both how it was shot and what it portrays. It speaks to the purity of the people, still hunting for food and relatively untouched by the modern world and possessions. The image transports me to another time. Ivan breaks the rules by putting a person in the middle of the frame and by cutting off half a body. Yet with the angled gun and machete in the foreground, and the hunter in the background giving dimension, the image is arresting”. (Photo by Ivan Kashinsky/National Geographic)

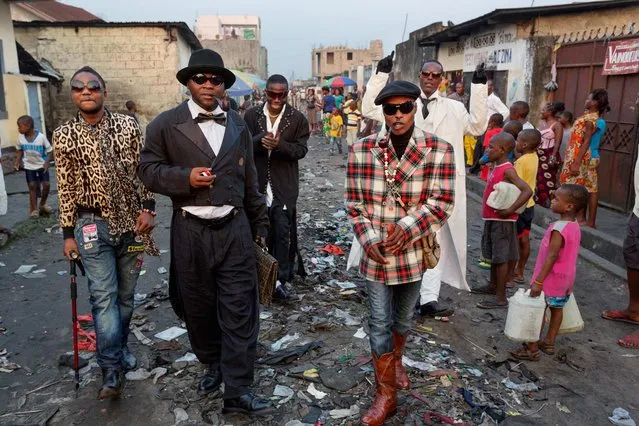

Since 1997, NASA has been sending rovers to Mars to document the soil, dig up rocks, and take pictures of the Martian landscape. But never before has a rover managed to take photos of itself. On August 8, 2012, the aptly named Curiosity touched down and made this ultimate selfie. Stitched together from 63 images, it shows the entire rover and even the imprints in the sand of its scoop and wheels – but not the seven-foot robotic arm that was holding the camera. As we all know, a self-portrait is not a unique achievement. But to take one from 34.8 million miles away is extraordinary. (Photo by NASA/JPL/Malin Space Science Systems (MSSS)/National Geographic)

Susan Welchman, Senior Editor: “Pascal Maitre shot this image of Julie Djikley, a street artist in Kinshasa. Julie covered her body with engine oil and wore cans on her breasts as a statement about pollution in our environment created by cars and traffic. On several occasions she carried a gas tank on her back and a steering wheel in her hands, pushing a tiny car made of old cans. In her seminaked state she drew jeers and disapproval from crowds on Kinshasa streets but she continued to walk in silence throughout the city. Recently her doctor suggested she stop this practice because the oil was entering her body through her skin, our largest organ. The image is effective without a caption, the composition both momentary and studied. I don’t get tired of looking at this photo because there are so many subtle colors and textures worth gazing at. Unable to see her eyes or what she is thinking, her smile communicates peace and purpose. Her body is that of a strong young woman and makes you wonder why she risks her well-being. Having traveled to Kinshasa twice I keep this image as a reminder of the strength of poor and concerned artists who continue to communicate what is on their minds amid danger and strife in that dense urban African life”. (Photo by Pascal Maitre/National Geographic)

Tardigrades are extremophiles. The tiny invertebrates can survive in both low- and high-pressure environments, and in temperatures as low as minus 328ºF (-200ºC) and as high as 304ºF (151ºC). But these millimeter-long, multicelled organisms have always been too elusively small to sit for a portrait. This year, however, German scientists used an electron microscope to make a high-resolution photograph of a single tardigrade – revealing a creature that resembles both a bear and a piglet. This image was published in July’s Visions of Earth, a trio of photos that appear in each issue of National Geographic. (Photo by Eye of Science/Science Source/National Geographic)

Mary McPeak, Photography Research Editor: “Having worked with Diane Cook and Len Jenshel on several stories, the tumbleweeds story is a favorite of mine. The photograph of the two masked workers in California holding a compact car-size tumbleweed above their heads catches your eye and makes you smile. The men seem to be surrounded by dangerous tumbleweeds almost inching toward them. It also illustrates what an invasive problem the weeds have become”. (Photo by Diane Cook/Len Jenshel/National Geographic)

06 Jan 2014 12:30:00,

post received

0 comments