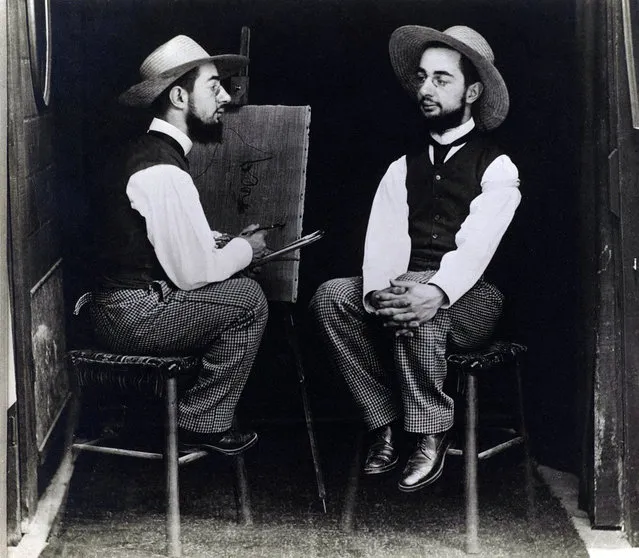

“Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec as Artist and Model” by Maurice Guibert, ca. 1890. The “duplex”, or “polypose”, picture was a popular trope that lent itself to endless comic variations and imaginative one-upmanship. The motif also appealed to artists, who occasionally created playful duplications of themselves. The French painter Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, who was also an avid amateur photographer, collaborated with his friend Maurice Guibert on this double portrait in which he plays the roles of both artist and model, each regarding the other with cool irony. (Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

“Soft Landing” by Oliver Wasow, 1987. The stock-in-trade of supermarket tabloids, images of UFOs test the relationship between photography and belief. In Soft Landing, as in his many other images of mysteriously floating disks and orbs, Wasow courts doubt by distorting found images, running them through a battery of processes, including photocopying, drawing, and superimposition. The resulting photographs play with the human propensity to invest form with meaning, offering just enough detail to spur the imagination. (Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

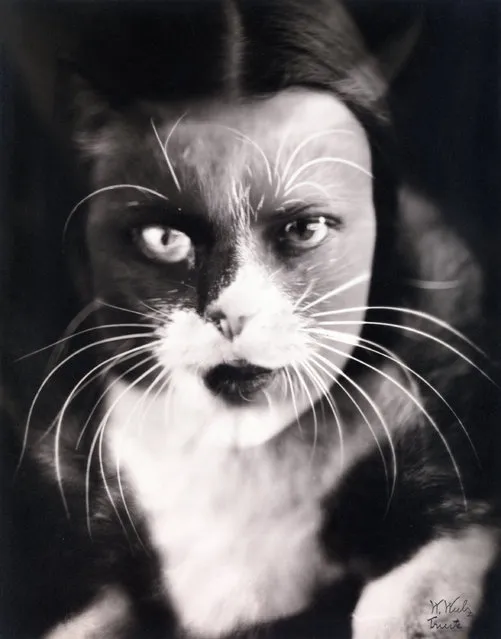

“Io + gatto” by Wanda Wulz, 1932. Wulz, a portrait photographer loosely associated with the Italian Futurist movement, created this striking composite by printing two negatives – one of her face, the other of the family cat – on a single sheet of photographic paper, evoking by technical means the seamless conflation of identities that occurs so effortlessly in the world of dreams. (Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

“Study for Holiday in the Wood” by Henry Peach Robinson, 1860. After the controversy stirred up by his depiction of a dying girl in Fading Away, Robinson chose a more anodyne rural scenario for his next major composition, A Holiday in the Wood. Over the course of two sunny days in April 1860, he exposed six separate negatives of models frolicking in his backyard studio. While waiting for another sunny day on which to photograph the woods a few miles away – it was an exceptionally rainy year – he made this trial print, on which he painted the wooded background by hand to help him envision the completed composition. The close correspondence between the study and the final image is evidence of Robinson’s precise preconception of his pictures. (Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

“Leap into the Void” by Yves Klein, 1960. As in his carefully choreographed paintings in which he used nude female models dipped in blue paint as paintbrushes, Klein's photomontage paradoxically creates the impression of freedom and abandon through a highly contrived process. In October 1960, Klein hired the photographers Harry Shunk and Jean Kender to make a series of pictures re-creating a jump from a second-floor window that the artist claimed to have executed earlier in the year. This second leap was made from a rooftop in the Paris suburb of Fontenay-aux-Roses. On the street below, a group of the artist’s friends from held a tarpaulin to catch him as he fell. Two negatives – one showing Klein leaping, the other the surrounding scene (without the tarp) – were then printed together to create a seamless “documentary” photograph. To complete the illusion that he was capable of flight, Klein distributed a fake broadsheet at Parisian newsstands commemorating the event. It was in this mass-produced form that the artist's seminal gesture was communicated to the public and also notably to the Vienna Actionists. (Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

“Room with Eye” by Maurice Tabard, 1930. (Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

“Red Square, Moscow, Russia” by F. Daziaro, ca. 1870. (Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

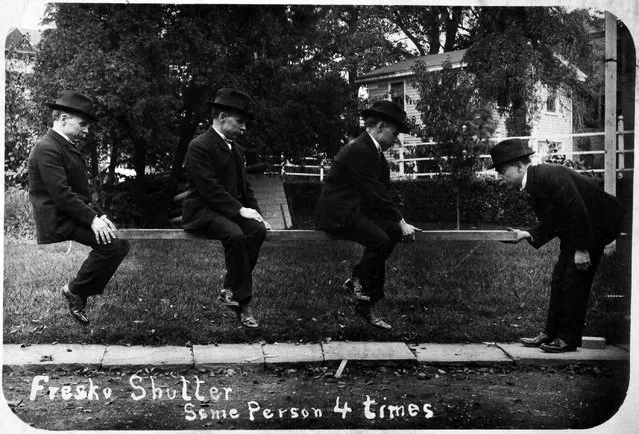

“Fresko Shutter, Same Person 4 Times” by Unknown, American, ca. 1890. (Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

“Man on Rooftop with Eleven Men in Formation on His Shoulders” by Unknown, American, ca. 1930. (Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

“Scene of Murder and Decapitation” by Unknown, French, ca. 1870. One can only guess at the strange psychosexual narrative that lay behind the making of this image and others in a private album that featured a small cast of characters repeatedly bound, beheaded, or burned at the stake, sometimes at the hands of their own doppelgangers. (Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

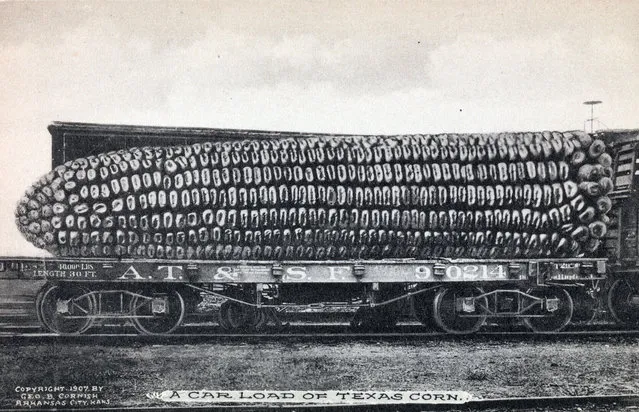

“A Car Load of Texas Corn” by George B. Cornish, ca. 1910. (Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

“The Sleepwalker” by George Platt Lynes, 1935. Lynes composed this picture from two negatives. The seams between them were airbrushed out so that his surprising anatomical conjunction would have the perfect aplomb of dream imagery. Alfred Barr's Museum of Modern Art exhibition Fantastic Art, Dada, and Surrealism (1936) included The Sleepwalker, probably a copyprint made by Lynes from this original. (Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

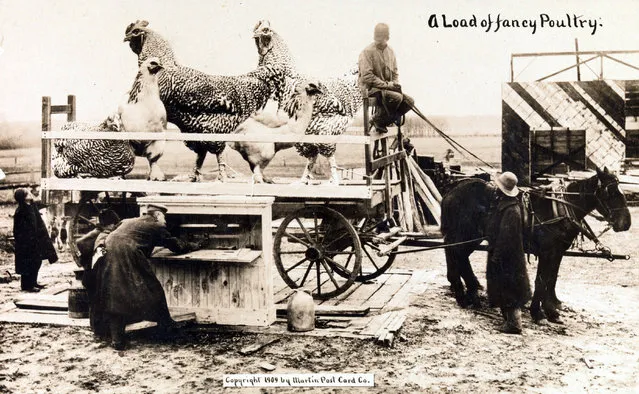

“A Load of Fancy Poultry” by William H. Martin, 1909. The tall-tale postcard was a uniquely American genre that flourished in the Midwest between about 1908 and 1915. The earliest master of the genre was William H. “Dad” Martin, a studio photographer in Kansas who established a successful sideline crafting photomontages of outlandish agricultural abundance. Intimately familiar with the tribulations of Midwestern farmers, including a fierce drought that parched the land for most of the 1890s, Martin lampooned the inflated promises of fertile soil, abundant rain, and hardy livestock that land companies used to lure settlers westward. (Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

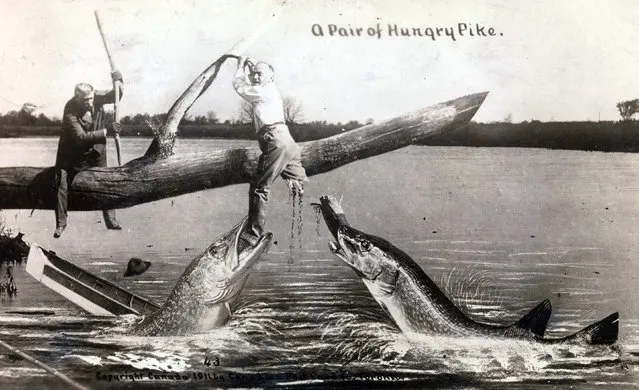

“A Pair of Hungry Pike” by Unknown, Canadian Post Card Company, 1911. (Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

“Man Daydreaming about Love” by Unknown, 1910s. (Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

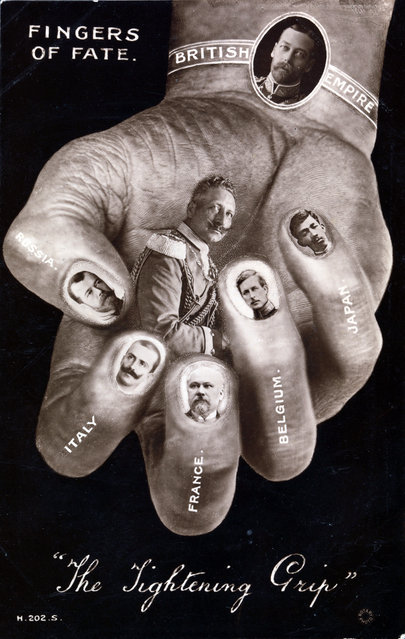

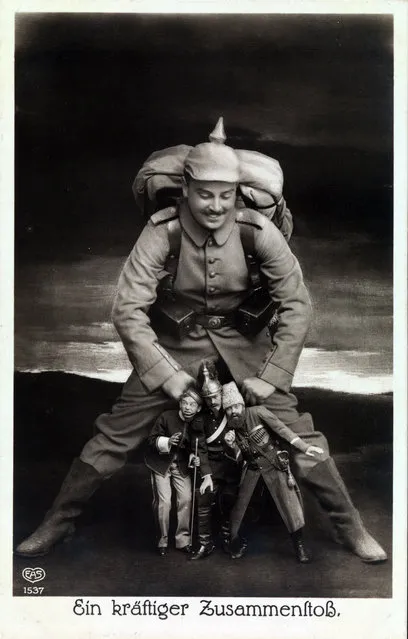

“Fingers of Fate – The Tightening Grip” by Unknown, ca. 1916. During World War I, European postcard publishers used photomontage to fan the flames of patriotism on both sides of the conflict. A postcard issued in Munich in 1914 shows a towering German infantryman pounding together the heads of three soldiers of the Triple Entente – France, England, and Russia – in what the caption calls a “powerful collision.” A few years later, an English publisher countered with a card on which a giant hand, its wrist and fingernails adorned with official portraits of the Allied leaders, crushes Germany’s Kaiser Wilhelm II in a “tightening grip”. (Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

“Dirigible Docked on Empire State Building, New York” by Unknown, American, 1930. In 1930 International News Photos transmitted over the wires this photograph of the U.S. Navy dirigible Los Angeles docked at a mooring mast atop the Empire State Building. In fact, no airship ever docked there, and the notion of the mast itself was a publicity stunt perpetrated by the building’s backers. In late 1929 Alfred E. Smith, the leader of a group of investors erecting the Empire State Building, announced that they would be increasing the building’s height by two hundred feet, making it slightly taller than its rival, the Chrysler Building. The tower’s extension was to serve as a mooring mast for zeppelins from which weary European travelers would be able to disembark via a gangplank into a private elevator that would whisk them to street level in just seven minutes. Ultimately, the unceasing gusty winds at the tower’s pinnacle made the plan impossible to execute, but the mast remained, allowing the Empire State Building to claim the title of world’s tallest skyscraper. (Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

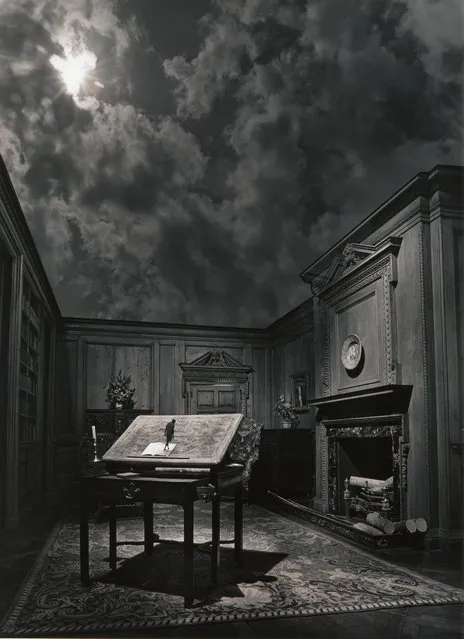

“Untitled” by Jerry N. Uelsmann, 1976. Uelsmann revived the technique of combination printing pioneered by such Victorian art photographers as Oscar Gustave Rejlander and Henry Peach Robinson in the early 1960s, when darkroom manipulation was denigrated by many proponents of straight photography as a flagrant violation of photographic purity. His pictures, which he creates in a darkroom equipped with seven enlargers, are filled with mind-bending paradoxes, oblique symbolism, and bizarre contrasts of scale. Uelsmann’s work is now considered an important precursor to the seamless compositing widely associated with digital photography and Photoshop. (Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

“Ein kräftiger Zusammenstoss” by Unknown; published by E. A. Schwerdtfeger & Co, Berlin, 1914. (Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

“Man Serving Head on a Platter” by William Robert Bowles, ca. 1900. (Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

“Woman Riding Moth” by Unknown, American, ca. 1950. (Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

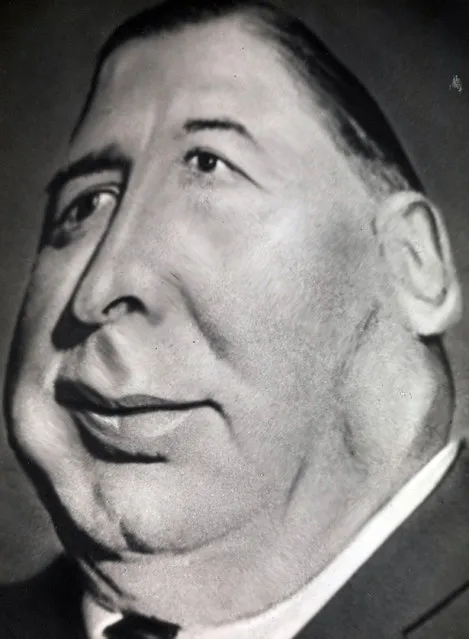

“Distortograph: William Hale “Big Bill” Thompson, Mayor of Chicago” by Herbert George Ponting, 1927. Best known for his dramatic photographs of the South Pole, Ponting was also an inveterate tinkerer. In 1927 he patented a lens attachment he dubbed the “variable controllable distortograph,” describing it as “a revolutionary optical system for photographing in caricature or distortion”. With his patent application, he submitted these caricatures of the flamboyantly corrupt mayor of Chicago William Hale “Big Bill” Thompson, known for his protection of the gangster Al Capone and for colorful campaign stunts, such as staging a mayoral debate with two live rats as his opponents. (Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

“Bruno Richard Hauptmann in Electric Chair” by John Wolters, 1936. In spite of the universal ban on cameras in American death chambers, news editors have long recognized the public’s hunger for eyewitness images of high-profile executions. When Bruno Richard Hauptmann was due to be executed for the kidnapping and murder of the young son of Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh, the International News Photos agency commissioned an artist to craft a photographic composite of the condemned man being strapped into the electric chair by two prison guards. The grisly image was created by staging the scene with actors then pasting headshots of Hauptmann and his executioners onto their bodies. (Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

“Crazy Camera: Secrets of Photomontage” by Claude A. Bromley, 1941. (Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

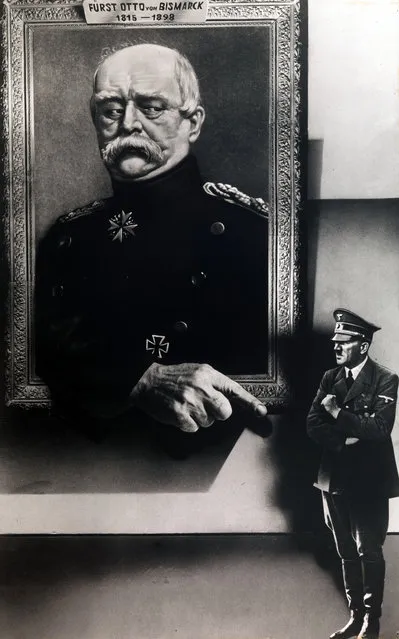

“The Corporal is Leading Germany into a Catastrophe” by Alexander Zhitomirsky, 1941. Working under the auspices of the Soviet propaganda ministry, Zhitomirsky produced posters and leaflets that were dropped from Soviet fighter planes as part of a campaign to demoralize German soldiers during World War II. Here, Germany’s “Iron Chancellor”, Otto von Bismarck (1815–1898), comes back to life in a painted portrait to point an accusing finger at the diminutive Führer (who never rose above the rank of corporal during his World War I army service), casting doubt on Hitler’s credentials as a military leader. (Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

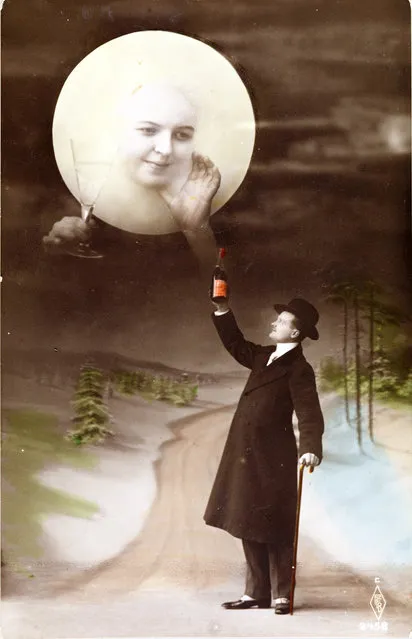

“Man Drinking with the Moon” by Unknown, 1910s. (Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

“Woman with Umbrella in Rain” by Raimund von Stillfried. Artist: Kusakabe Kimbei (Japanese, 1841–1934), 1870s. Commercial photography studios in Meiji-era Japan were renowned for the subtlety and refinement of their coloring techniques. This hand-tinted image of a young woman caught in a heavy rainstorm achieved its naturalistic effect by knitting together multiple strands of artifice: the greenery in the foreground was a studio prop; the flaps of the kimono were suspended by thin wires to create the impression of a strong wind; and long, diagonal marks were made on the negative to suggest streaks of rain. (Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

“Group of Thirteen Decapitated Soldiers” by Unknown, ca. 1910. (Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

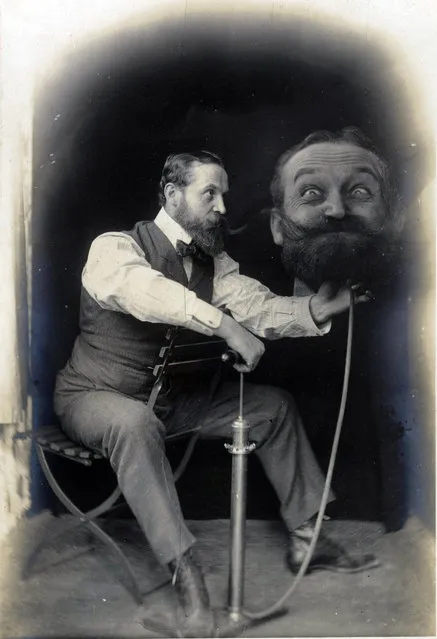

“Un Coup de Pompe, S.V.P.” by Unknown, French, 1899. Around the turn of the twentieth century, decapitation was a hugely popular theme among photographers, stage magicians, and early filmmakers such as Georges Méliès. This photograph of a bearded gentleman tenderly inflating an enlarged duplicate of his own head with a bicycle pump graced the cover of the amateur photography magazine Photo Pêle-Mêle in 1903. Apparently, balloon heads were in the air in Belle Époque Paris. Two years earlier, Méliès had produced a short film, L’homme à la tête de caoutchouc (The Man with the Rubber Head, 1901), in which a scientist inflates a replica of his own head with a bellows. (Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

“Same Man Five Times in Judge Costume” by Unknown, French, 1880s. Photographs were only subject to legal deposit arrangements in the Bibliothèque Nationale de France from 1925 onwards. However, photographers voluntarily deposited their works in the 19th century. Per an email from April 25, 2012 from the department of photographs at the BNF, this work is of unknown provenance, and it does not have any record of previous exhibitions. They note, that unlike museums, they do not keep a file about each object in their collection. (Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

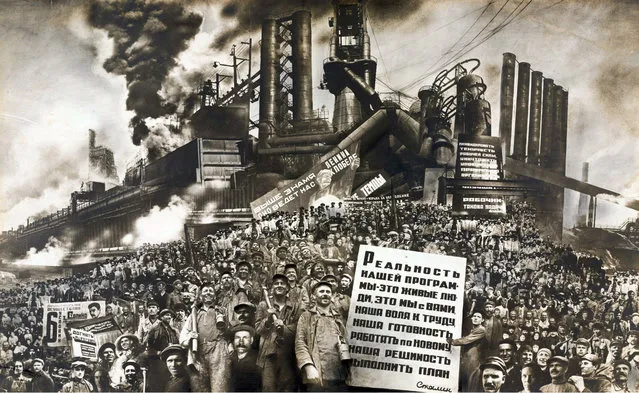

“The Reality of Our Plan is Active People” by Mikhail Rozulevich, 1933. Razulevich initially produced this photomontage in 1932 to decorate Leningrad’s Uritsky Square (now Saint Petersburg’s Palace Square) for the fifteenth anniversary of the October Revolution. The artist combined more than three hundred images from the state archives into an enormous, seamless whole, about twenty-three yards long. The industrial landscape in the background was a composite of several images of the major construction projects undertaken as part of Stalin’s first Five-Year Plan (1928–32). Smaller copies of the photomural were installed in train stations throughout the city. (Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

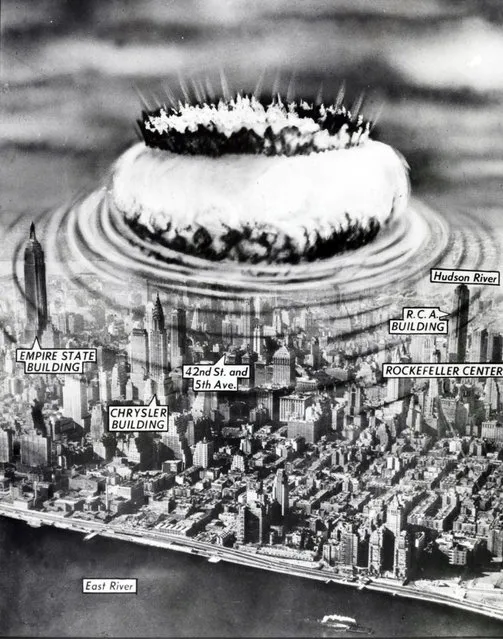

“New York Nightmare: Air-burst Atomic Bombs Make Cities in the Northeast Obsolete...” by John Carlton, 1949. The sheer impossibility of photographing the future did not stop picture editors from fabricating speculative representations of things to come. In the decades following the detonation of “Little Boy” at Hiroshima, Japan, the era’s technological optimism was shadowed by a profound fear of nuclear devastation. This photo illustration from the archives of London’s Daily Herald gives striking visual form to the pervasive doomsday anxiety of the atomic age. (Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

“Unidentified Woman Seated with a Female Spirit” by William Mumler, 1862-75. In the early 1860s Mumler became the first producer and marketer of “spirit photographs”, portraits in which hazy figures, presumed to be the spirits of the deceased, loom behind or alongside living sitters. He quickly garnered the support of the burgeoning Spiritualist movement, which held that the human spirit exists beyond the body and that the dead can – and do – communicate with the living. Mumler first discovered his calling while working as a jewelry engraver in Boston, but his career there was cut short when a ghost that had appeared in two of his photographs was discovered to be a local resident who was still very much alive. In 1868 he opened a studio in New York City but was arrested the following year on charges of fraud and larceny. (Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

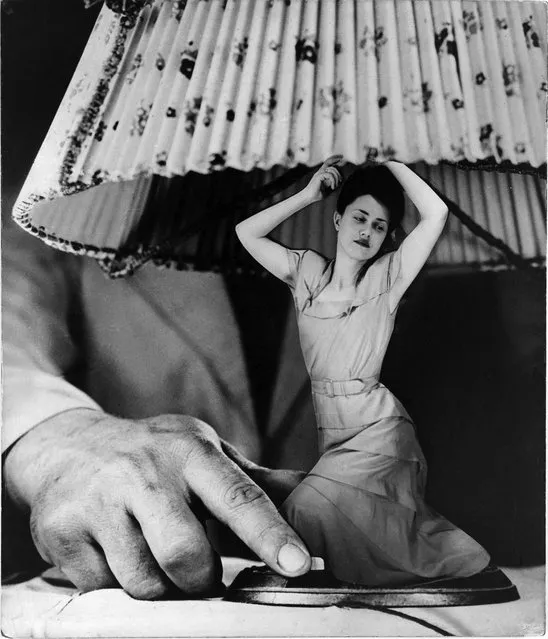

Sueño No. 1: “Articulos eléctricos para el hogar” by Grete Stern, ca. 1950. In 1948 the Argentine women’s magazine Idilio introduced a weekly column called “Psychoanalysis Will Help You”, which invited readers to submit their dreams for analysis. Each week, one dream was illustrated with a photomontage by Stern, a Bauhaus-trained photographer and graphic designer who fled Berlin for Buenos Aires when the Nazis came to power. Over three years, Stern created 140 photomontages for the magazine, translating the unconscious fears and desires of its predominantly female readership into clever, compelling images. Here, a masculine hand swoops in to “turn on” a lamp whose base is a tiny, elegantly dressed woman. Rarely has female objectification been so erotically and electrically charged. (Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

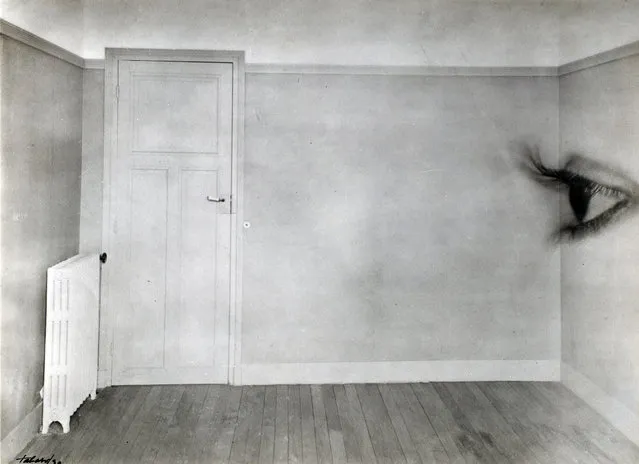

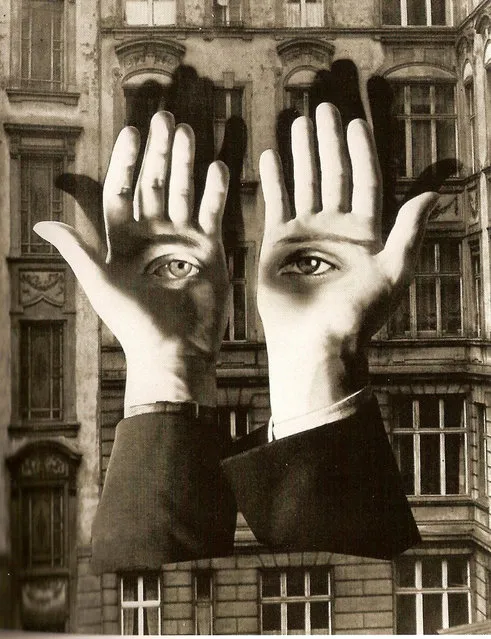

“Lonely Metropolitan” by Herbert Bayer, 1932. A Bauhaus-trained graphic designer who immigrated to New York City in 1938, Bayer was known for his innovative work in advertising and book publishing. Although never formally connected with Surrealism, he was fascinated by dream imagery and embraced photomontage as a means of visualizing the psychological realities of modernity. In 1931 he began a series of photomontages illustrating his own dreams, which included this emblematic image in which the artist’s eyes stare from the palms of his hands, cut off at the wrists and floating mysteriously in the courtyard of a Berlin apartment block. (Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

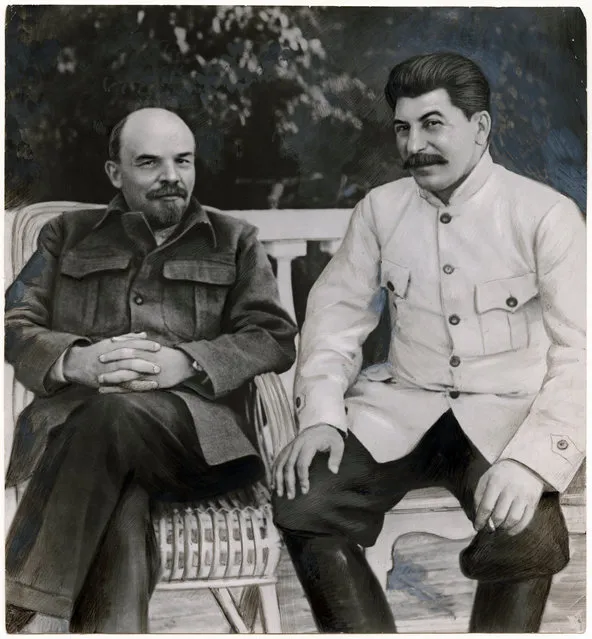

“Lenin and Stalin in Gorky, 1922” by Unknown, Russian, 1949. In this widely reproduced image, Joseph Stalin and Vladimir Ilich Lenin – the leader of the Bolshevik Revolution and founder of the U.S.S.R. – appear to share a friendly moment together outdoors at Gorki, Lenin’s estate just south of Moscow. Although Stalin did visit Lenin there frequently, the photograph has been heavily reworked: retouchers smoothed Stalin’s pockmarked complexion, lengthened his shriveled left arm, and increased his stature so that Lenin seems to recede benignly beside his trusted heir apparent. The reality was quite different: in a letter dictated around the time the picture was taken, Lenin described Stalin as intolerably rude and capricious and recommended that he be removed from his position as the Communist Party’s secretary general. (Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

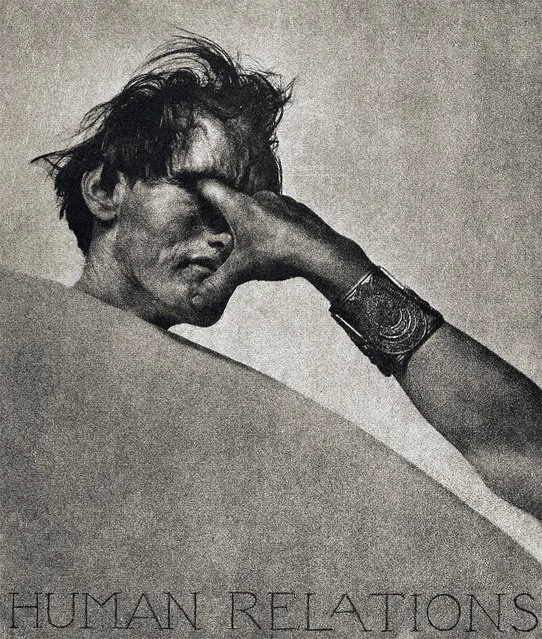

“Human Relations” by William Mortensen, 1932. Mortensen began his career as a Hollywood studio photographer, turning out glamour portraits of stars such as Clara Bow and Jean Harlow. In the early 1930s he established a photography school in Laguna Beach, where he refined and promoted his own aesthetic—an eccentric blend of late Pictorialism, Surrealism, and Hollywood kitsch. Restlessly inventive in the darkroom, he employed a wide variety of techniques, including combination printing, heavy retouching, and physical and chemical abrasion of the negative. At times, his use of textured printing screens gave his photographs the appearance of etchings or lithographs, as in this audaciously grotesque picture, which was prompted, according the artist, by an overcharged long-distance telephone bill. (Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

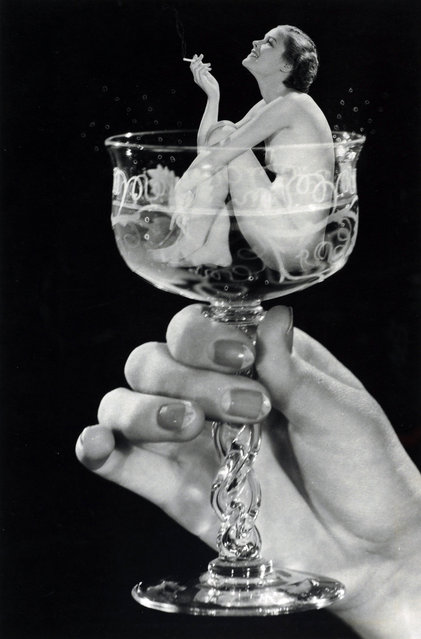

“Woman in Champagne Glass” by Howard S. Redell, ca. 1930. Redell, a photographer and sales manager at Underwood and Underwood Studios, harnessed the power of s*x appeal in this photomontage of an attractive young woman enjoying a cigarette while bathing in a glass of champagne – a pictorial fantasy of luxury and indulgence that was probably created as a tobacco advertisement. (Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

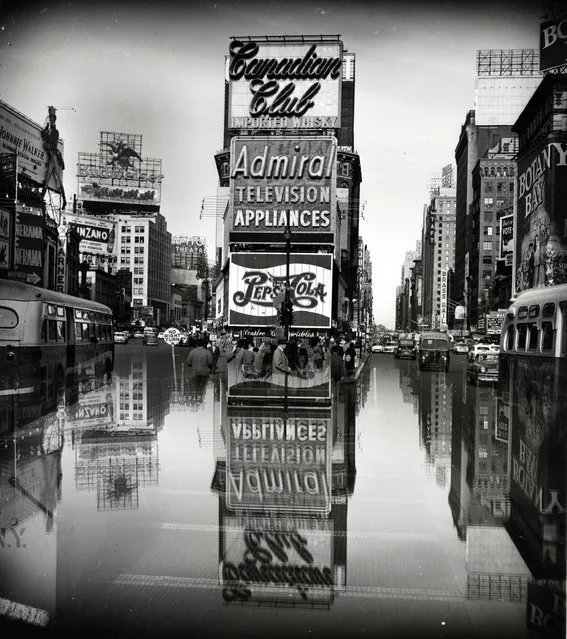

“Times Square, New York” by Weegee, 1952–59. Famous for his gritty tabloid crime photographs, Weegee devoted the last twenty years of his life to what he called his “creative work”. He experimented prolifically with distorting lenses and comparable darkroom techniques, producing photo caricatures of politicians and Hollywood celebrities, novel variations on the man-in-the-bottle motif, and uncanny doublings and reflections, such as this striking image, which he described as “Times Square under 10 feet of water on a sunny afternoon”. (Photo courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

12 May 2013 10:13:00,

post received

0 comments