Kutubdia, an island of fishing villages and salt farms, has halved in size in 20 years, with family homes destroyed by ever-encroaching tides. In nearby Cox’s Bazar, more frequent storms have had a severe impact on fishermen’s catches. Here: Fishermen in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, say an increase in storms and storm warnings – which mean it is too dangerous to enter the deep sea – has affected their livelihoods. Last year there were a record four cyclones in the Bay of Bengal. In 2015, there was just one. (Photo by Noor Alam/Majority World)

Owners at the dry fish yards in Cox’s Bazar say the changing weather has had a big impact on business in recent years. They blame higher storm surges on a rapid rise in sea levels, which has flooded the land and ruined the fish. Because the rains have started coming even in the dry season, it has become difficult to dry what catches they have. (Photo by Noor Alam/Majority World)

Villagers cross the bridge linking Kutubdia shanty town, in Cox’s Bazar, with the dry fish yards, where many of them work. (Photo by Noor Alam/Majority World)

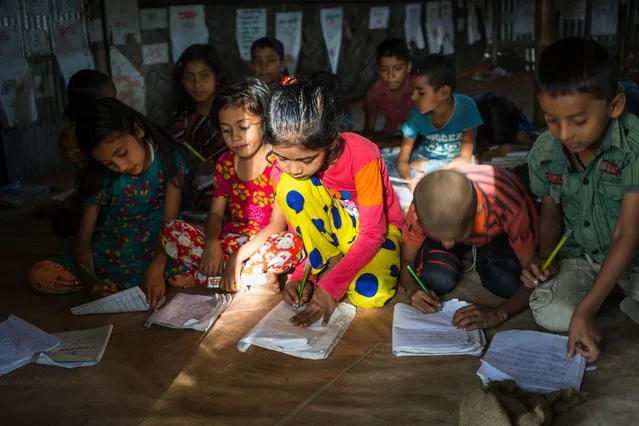

Children learning English at the school in Kutubdia para, or neighbourhood, Cox’s Bazar. Many villagers are migrants who fled nearby Kutubdia island after they lost their lands when a cyclone hit in 1991. (Photo by Noor Alam/Majority World)

A woman prepares a meal in Kutubdia para. The shanty town is home to an estimated 40,000 people but has no health centre. (Photo by Noor Alam/Majority World)

The Bangladesh government has built a sloped, three-metre high embankment to protect Kutubdia island from the rapidly rising tide. (Photo by Noor Alam/Majority World)

A row of mangrove trees are all that remains of a village in the Ali Akbar Dale area, southern Kutubdia island, which disappeared under the sea five years ago. The sea level in nearby Cox’s Bazar is one of the fastest rising in the world. Villagers who lost their ancestral land now live on the embankment. (Photo by Noor Alam/Majority World)

A flooded village in Ali Akbar Dale that was hit by a storm surge. Bangladesh is ranked among the most climate vulnerable nations in the world, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (Photo by Noor Alam/Majority World)

A cyclone shelter on Kutubdia island, installed as part of a government scheme that, alongside warning systems, has dramatically reduced lives lost during cyclones in the country. (Photo by Noor Alam/Majority World)

A makeshift house built on top of the embankment of Kutubdia. Sandbags have been piled up to try to protect the temporary dwelling from flooding. Many villagers here are landless, and therefore forced to occupy the only ground available, which is often the most vulnerable to extreme weather. (Photo by Noor Alam/Majority World)

Villagers from the fishing communities of Ali Akbar Dale. They have to move their homes several times a year because of flooding from the high tides. They fear the sea-level rise will swallow the island altogether. (Photo by Noor Alam/Majority World)

Villagers in Ali Akbar Dale have piled up sandbags at the most vulnerable spots, where the concrete embankment has been breached, to try to stop water flooding their homes. (Photo by Noor Alam/Majority World)

A man builds a new house in Ali Akbar Dale. The extreme weather events that have had such an impact on communities here are predicted to increase with climate change. (Photo by Noor Alam/Majority World)

The construction of concrete blocks, on a coastal road in Cox’s Bazar. Environmental campaigners who help the communities here say repairs to the embankments are frequently needed after they are breached by the sea. (Photo by Noor Alam/Majority World)

Fields of salt farms on Kutubdia. Farmers say they changed their land use 10 years ago, when sea water entered the agricultural land, spoiling the crops. (Photo by Noor Alam/Majority World)

Salt farming is more lucrative, the farmers say, but makes for back-breaking and time-consuming work. (Photo by Noor Alam/Majority World)

For centuries, the ocean has supported the livelihoods of the people of Kutubdia para, in Cox’s Bazar, and Kutubdia island. But the rising sea levels along the coast have brought fresh challenges. UN scientists predict some of the worst impacts of climate change will occur in south-east Asia. They believe more than 25 million people in Bangladesh will be at risk from sea-level rise by 2050. (Photo by Noor Alam/Majority World)

A boy looks for valuables thrown in the polluted waters of Buriganga river on January 22, 2016 in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Buriganga river, which flows by Dhaka, is one of the most polluted rivers in Bangladesh because of dumping of industrial dumping and human waste. Most of the riverbed is lost to encroachment and the remaining suffers from municipal and factory waste dumped through storm drains. More than 140 million people depend on the rivers for their livelihood and for transportation. (Photo by Shams Qari/Barcroft Images)

Rohingya and Bangladeshis work side by side as fishermen near the Shamlapur refugee camp on January 17, 2017 in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh. More than 65,000 Rohingya Muslims have fled to Bangladesh from Myanmar since October last year, after the Burmese army launched a campaign it calls “clearance operations” in response to an attack on border police on October 9, believed to have been carried out by Rohingya militants. Waves of Rohingya civilians have since fled across the border, most living in makeshift camps and refugee centers with harrowing stories of the Burmese army committing human-rights abuses, such as gang rape, arson and extrajudicial killing. The Rohingya, a mostly stateless Muslim group numbering about 1.1 million, are the majority in Rakhine state and smaller communities in Bangladesh, Thailand and Malaysia. The stateless Muslim group are routinely described by human rights organizations as the 'most oppressed people in the world' and a “minority that continues to face statelessness and persecution”. (Photo by Allison Joyce/Getty Images)

Bangladeshi vegetable vendors wait for customers at a wholesale market in Dhaka on January 22, 2017. Dhaka Kawran Bazar is a major business district and wholesale market place in Dhaka. (Photo by AFP Photo/Stringer)

A woman reacts to the camera while preparing to cook, next to a railway track in Kawran Bazar, as a train passes by in Dhaka, Bangladesh January 17, 2017. (Photo by Mohammad Ponir Hossain/Reuters)

A street vendor returns change money to a customer after selling ready-made garments in Dhaka, Bangladesh January 17, 2017. (Photo by Mohammad Ponir Hossain/Reuters)

A worker unloads stone from a ferry at the Buriganga River in Dhaka, Bangladesh, January 18, 2017. (Photo by Mohammad Ponir Hossain/Reuters)

A Bangladeshi woman and her child walks on a mustard field in Munshiganj near Dhaka, Bangladesh, January 20, 2017. (Photo by Mohammad Ponir Hossain/Reuters)

A vegetable seller cuts off the leaves of kohlrabi before selling it at Kawran Bazar in Dhaka, Bangladesh January 25, 2017. (Photo by Mohammad Ponir Hossain/Reuters)

A vendor weighs vegetables as he sells them out at Kawran Bazar in Dhaka, Bangladesh January 25, 2017. (Photo by Mohammad Ponir Hossain/Reuters)

A boy carries balloons for sale in the streets of Dhaka Bangladesh, January 25, 2017. (Photo by Mohammad Ponir Hossain/Reuters)

Street vendors carry chickens for sale at Kawran Bazar in Dhaka, Bangladesh January 25, 2017. (Photo by Mohammad Ponir Hossain/Reuters)

A vendor sells vegetables at Kawran Bazar in Dhaka, Bangladesh January 25, 2017. (Photo by Mohammad Ponir Hossain/Reuters)

28 Jan 2017 07:15:00,

post received

0 comments