Brazilian jaguars, imperilled by hunters, ranchers and destruction of their habitat, have learned to survive at least one menace – flooding in the Amazon. They take to the trees. Although they can be six feet long and 200 pounds, the largest South American cats nimbly navigate treetops where they stay from April to July when the rainforest floor is under meters-deep water. “It shows that even as a large animal, the jaguar can withstand the flooding – feeding, breeding and raising its young in the treetops for three to four months”, says Emiliano Ramalho, the lead researcher for Project Iauarete, which is administered by the Instituto Mamirauá. “This had never been documented before we began researching the jaguars here”. The Iauaretê Project monitors jaguars in Mamirauá, studies their relationship with local residents and undertakes conservation for the species, which lives deep in the rainforest. Documenting jaguar behavior during the rainy season is rare, with their long-term stays in the treetops first recorded by the researchers in 2013 after nine years of monitoring in the region. Called “painted jaguars” in Brazil because of their intricately spotted fur, jaguars are difficult to see in the dense jungle canopy. Researchers discovered their behavior after nearly a decade of studying them from floating bases, braving the same conditions that put flood waters at the doorsteps of more than 10,000 people living in the Mamirauá reserve. On one expedition last month, researchers with headlamps tracked down and tranquilized a black male jaguar at night, placed his limp body on a blue tarp and wrapped his head in a towel as they fitted him with a black tracking collar, measured his teeth and checked his vitals. So many jaguars have been fitted with trackers that researchers can now pinpoint them by holding up pronged radio receivers as they pilot small boats through the flooded forest. Ramalho says that understanding this behavior is further evidence supporting the need to preserve the Amazon floodplain. The Iauaretê Project has teamed up with the Uakari Lodge in the reserve, which is operated by an association of local residents, to offer ecotourism trips that take advantage of the trackers to allow tourists to catch a glimpse of the animals. The goal is to raise awareness for conservation and generate income for residents. A trip to see jaguars living in trees costs 10,000 reais ($3,000) per person. Ecotourism fosters better relations between jaguars and residents, who are sometimes fearful or angry because jaguars can eat livestock and pets. Here: A female adult jaguar sits atop a tree at the Mamiraua Sustainable Development Reserve in Uarini, Amazonas state, Brazil, June 5, 2017. (Photo by Bruno Kelly/Reuters)

Tourists with local guides search for jaguars on top of the trees at the Mamiraua Sustainable Development Reserve in Uarini, Amazonas state, Brazil, May 19, 2016. (Photo by Bruno Kelly/Reuters)

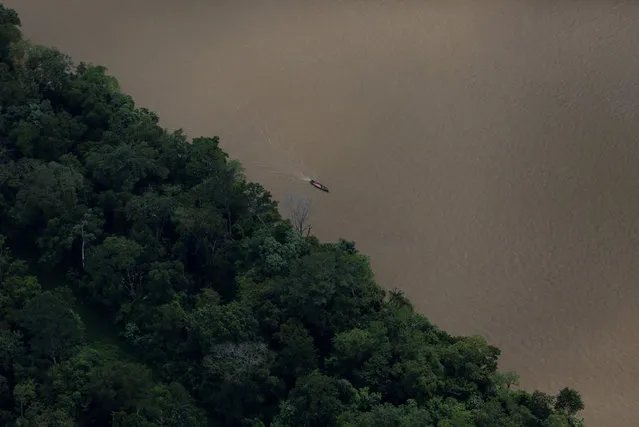

A boat sails past the Mamiraua Sustainable Development Reserve in Uarini, Amazonas state, Brazil, May 16, 2016. (Photo by Bruno Kelly/Reuters)

A black male jaguar looks out from atop a tree at the Mamiraua Sustainable Development Reserve in Uarini, Amazonas state, Brazil, June 7, 2017. (Photo by Bruno Kelly/Reuters)

Lead researcher Emiliano Esterci Ramalho from the Mamiraua Institute uses a radio device to locate jaguars at the Mamiraua Sustainable Development Reserve in Uarini, Amazonas state, Brazil, May 30, 2017. (Photo by Bruno Kelly/Reuters)

Researcher Diogo Maia Grabin (L) and his assistant Railgler dos Santos from the Mamiraua Institute install camera traps at the Mamiraua Sustainable Development Reserve in Uarini, Amazonas state, Brazil, February 9, 2018. (Photo by Bruno Kelly/Reuters)

An alligator, part of the jaguars' diet, surfaces at the Mamiraua Sustainable Development Reserve in Uarini, Amazonas state, Brazil, February 11, 2018. (Photo by Bruno Kelly/Reuters)

A heron is seen in the Mamiraua Sustainable Development Reserve in Uarini, Amazonas state, Brazil, March 7, 2018. (Photo by Bruno Kelly/Reuters)

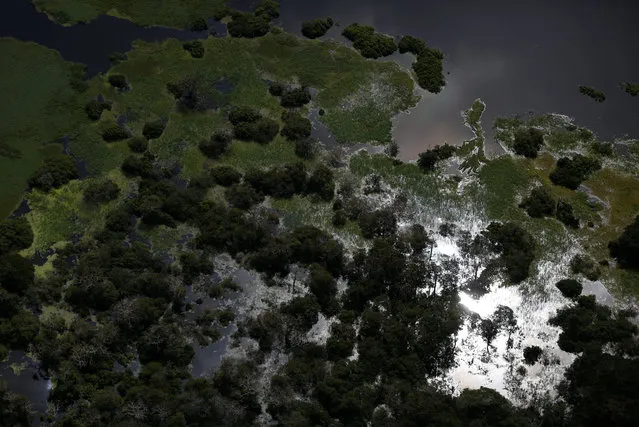

The Mamiraua Sustainable Development Reserve is seen in Uarini, Amazonas state, Brazil, May 16, 2016. (Photo by Bruno Kelly/Reuters)

Yellow-hooded blackbirds fly over the Mamiraua Sustainable Development Reserve in Uarini, Amazonas state, Brazil, February 25, 2018. (Photo by Bruno Kelly/Reuters)

A black male jaguar climbs down a tree branch at the Mamiraua Sustainable Development Reserve in Uarini, Amazonas state, Brazil, June 1, 2017. (Photo by Bruno Kelly/Reuters)

Research assistant Railgler dos Santos from the Mamiraua Institute installs traps to catch jaguars at the Mamiraua Sustainable Development Reserve in Uarini, Amazonas state, Brazil January 22, 2018. (Photo by Bruno Kelly/Reuters)

A camera installed in a trap captures a glimpse of a jaguar at the Mamiraua Sustainable Development Reserve in Uarini, Amazonas state, Brazil, Feb.13, 2018. (Photo by Handout/Reuters)

A jaguar cub, stands atop a tree during a flood at the Mamiraua Sustainable Development Reserve in Uarini, Amazonas state, Brazil, June 5, 2017. (Photo by Bruno Kelly/Reuters)

Researcher Diogo Maia Grabin prepares to tranquillise a black male jaguar at the Mamiraua Sustainable Development Reserve in Uarini, Amazonas state, Brazil, March 6, 2018. (Photo by Bruno Kelly/Reuters)

A black male jaguar lies tranquillised by researchers from the Mamiraua Institute at the Mamiraua Sustainable Development Reserve in Uarini, Amazonas state, Brazil, March 6, 2018. (Photo by Bruno Kelly/Reuters)

A researcher from the Mamiraua Institute captures a black male jaguar at the Mamiraua Sustainable Development Reserve in Uarini, Amazonas state, Brazil, March 6, 2018. (Photo by Bruno Kelly/Reuters)

Veterinarian Louise Maranhao from the Mamiraua Institute examines a black male jaguar after capturing him at the Mamiraua Sustainable Development Reserve in Uarini, Amazonas state, Brazil, March 6, 2018. (Photo by Bruno Kelly/Reuters)

A researcher from the Mamiraua Institute puts a GPS collar on a black male jaguar after capturing him at the Mamiraua Sustainable Development Reserve in Uarini, Amazonas state, Brazil, March 6, 2018. (Photo by Bruno Kelly/Reuters)

A researcher from the Mamiraua Institute examines a black male jaguar after capturing him at the Mamiraua Sustainable Development Reserve in Uarini, Amazonas state, Brazil, March 6, 2018. (Photo by Bruno Kelly/Reuters)

The Mamiraua Sustainable Development Reserve is seen in Uarini, Amazonas state, Brazil, May 16, 2016. (Photo by Bruno Kelly/Reuters)

A female adult jaguar, which has a cub, growls at the Mamiraua Sustainable Development Reserve in Uarini, Amazonas state, Brazil, June 5, 2017. (Photo by Bruno Kelly/Reuters)

07 Apr 2018 00:03:00,

post received

0 comments