Magbola Alhadi, 20, and her three children pose for a portrait in Jamam refugee camp in Maban County, South Sudan on August 11th, 2012. Magboola and her family weathered aerial bombing raids for several months, but decided it was time to leave their village of Bofe the night that soldiers arrived and opened fire. With her three children, she travelled for 12 days from Bofe to the town of El Fudj, on the South Sudanese border. The most important thing that Magboola was able to bring with her is the saucepan she holds in this photograph. It wasn't the largest pot that she had in Bofe, but it was small enough she could travel with it, yet big enough to cook sorghum for herself and her three daughters (from left: Aduna Omar, 6, Halima Omar, 4, and Arfa Omar, 2) during their journey. (Photo by Brian Sokol/Panos Pictures)

Howard Serad, 21, poses for a portrait in Yusuf Batil refugee camp in Maban County, South Sudan on August 6th, 2012. Exchanges of gunfire and aerial bombardment forced Howard, with his wife and six children, to flee their home in Bau County, in Sudan's Blue Nile State, four months earlier. At the time of this photograph, two of Howard's children were suffering from diarrhea. The most important object that Howard was able to bring with him is the long knife he holds, called a “shefe”, with which he was able to defend his family and his herd of 20 cattle during their 20 day journey from Bau County to the South Sudanese border. (Photo by Brian Sokol/Panos Pictures)

Malian refugee Abdou Ag Moussa, 34, poses for a portrait with his family outside of their shelter in Mentao refugee camp, Burkina Faso, on the 15th of March, 2013. Abdou’s family are nomadic Tuareg herders from Ebangamallan encampment, near Gosi, Mali. On the morning of January 25th, 2012, Abdou was tending to the family’s camels several hours away from their camp, and his father, Abdo Samad Ag Mohammed Asalek, 64, was away looking after the family’s cattle. That day, while observing prayers, Abdou’s mother, Zikra Wallet Mohammed, 40, and five other women, were abducted by armed men. They were taken a short distance from the encampment, and shot. Abdou’s mother, and four others, were killed. One of the women survived, but lost a leg. When Abdou learned what had happened, he waited until dark and then returned to the camp, loading his wife and two children onto a donkey in secret, then escaping into the desert. When the gunmen departed three days later, Abdou returned to bury his mother’s body. It had been left in the sun, and attacked by animals. He recalls counting 30 bullet holes. “For seven days and nights, I didn’t sleep. I only prayed, and thought. Even now, I barely sleep. When I fled from Mali, my hair was black. In only a year look how much of it has turned grey, like it is mixed with ashes”, he says. The most important object that Abdou was able to flee Mali with is the motorcycle that he and his family sit upon in this photograph. After burying his mother, Abdou put his wife and children into a car. He and his father followed on the motorcycle, which he says saved their lives. (Photo by Brian Sokol/Panos Pictures)

Gerembo (family name) Jean (given name), 36, poses for a portrait in Batanga transit center for Central African refugees, Equateur Province, Democratic Republic of Congo on 9 August, 2013. Jean recalls the date perfectly, it was Wednesday the 27th of March, 2013 when Seleka forces entered his village of Batalimo. On that day his wife and two children were staying with his mother-in-law, while he was at the home that the four of them share with his widowed mother. The only of five children to survive to adulthood, Jean made his living as a fisherman, and helped his mother with a small business selling palm oil out of their home. The Seleka heard from one of their neighbors that Jean's mother had saved some money, and at 11:45 that night there came a knock at the door. Jean hid beneath his mother's bed and told her to remain silent, and not to answer it. A few moments later, the door was kicked in, and several men entered the dark house waving flashlights. One of the soldiers walked over to the bed and slit the old woman's throat. Terrified, Jean stayed under the bed as they looted the home. At some point, they found his mother's savings and left without discovering him. For the duration of the night he stayed under the bed of his slain mother, gathering the courage to leave the house early the next morning. He found 8 young people who were, as he said, “brave enough to to help me to bury my mother. Meanwhile, his wife had heard of her mother-in-law's murder and fled to the bush with their two children. After the burial, Jean found his family, gathered a few essentials from his wife's mother's house, and together they fled across the Oubangi River in his small fishing boat. The most important thing that Jean was able to bring with him from CAR is the fishing net that he holds in this photograph. He says that the net allows him to live, and to earn. “Some of the fish I sell, some we eat. I use the money to buy clothes and to pay the local people (in Batalimo, DRC) for the plantains, cassava and peanuts we get from their land”. Traumatized by the death of his mother, Jean lives in fear of a return to CAR. Several weeks before this photograph was taken, he was spotted by Seleka troops while fishing. They pointed their guns at him and demanded that he come ashore, at which point they beat him severely and took his catch. “I pray to God to help me”, he says. “Who knows when we will be able to go back? Only God knows. I have to accept to live here (DRC) until peace returns”. Conflict in CAR has caused a mass displacement of people to neighboring DRC. Some 40,000 CAR residents have fled to DRC since April 2013, when Seleka rebels ousted the CAR government. UNHCR and its partners are building four refugee camps in DRC’s Equateur and Oriental Provinces to provide protection and assistance to the refugees and ease the burden on the local population. The process of getting refugees to the camps, however, is not an easy one. Immediately afar fleeing CAR, many refugees take shelter in “transit centers” immediately across the border in DRC. These locations are extremely close to CAR. For their security, refugees are relocated a safe distance from the border to camps, such as Boyabo, where their needs can be better tended to. In Boyabo, families will be provided with a private shelter, non-food items (NFIs), and receive access to health care and more nutritious food. (Photo by Brian Sokol/Panos Pictures)

Haja Tilim, 55, poses for a portrait in Jamam refugee camp in Maban County, South Sudan on August 7th, 2012. When a bomb was dropped on the home of her neighbor Issa Unis, he was killed instantly. That night, Haja and her family fled their home in Fadima Village, in Sudan's Blue Nile State. The most important thing that Haja was able to bring with her is the patterned shawl, called a “taupe” which which she carried her 18 month old granddaughter, Bal Gaze. Haja brought nothing else with her, not even wearing shoes during the family's 25-day journey from Fadima to the South Sudanese border. She recalls, “I started to run while wearing my sandals, but they slowed me down, so I threw them on the side of the trail”. (Photo by Brian Sokol/Panos Pictures)

Poga Za (family name) Fideline (given name), 13, poses for a portrait in Batanga transit center for Central African refugees in Equateur Province, Democratic Republic of Congo on 12 August, 2013. When Seleka forces arrived in Fideline's village, her family hoped that they would be able to stay in Moungoumba and peacefully coexist with the armed men. A week later, on the 7th of April, 2013, this proved impossible. Fideline and some other children were playing near the river when Seleka forces got into an argument with a Central African businessman. When the businessman refused to give his money to the gunmen, the dragged him from the port to the village center. As Fideline and her friends watched, they tied his arms behind his back, then threw him facedown to the ground, and shot him twice in the back. Terrified, the children ran in all directions. Fideline remembers screaming as she sprinted home, where she told her family what had happened as she trembled and sobbed. Her father immediately decided that they had to leave. Fideline, her three sisters, three brothers, mother and father grabbed a few belongings before running from their home and hiding overnight in the forest beyond the village. At 9:00 the next morning, they boarded a boat, and two hours later arrived safely at Batanga. The most important thing that Fideline was able to leave her home with are the notebooks that she holds in this photograph. An excellent student, Fideline one day hopes to be a minister in her country's government. “I couldn't take my school bag, my shoes, or the colored ribbons for my hair”, she recalls, “but I did bring my notebooks and my pen”. Holding her history, homework and practice books – all of which bear an image of the African continent on their covers – she says, "we have suffered so much. My father is out of work and my mother goes to the fields all day. I want to study so that I can become someone. I want to study”. (Photo by Brian Sokol/Panos Pictures)

Mputu Jeanne, Mother, b. 23 March 1960 in Makela Dzombo, Ouige Province; Joelle Yamni Ombi, Daughter, b. 17 January 1986; Laeticia Nzapaombi, Daughter, b. 22 March 1988. Jeanne was born in Angola, but fled when she was six years old. “I don’t really remember anything of Angola because I was too young (when we left). Mama said, ‘We have to go, people are dying here,’ and we left,’” she says. Her two daughters were both born as refugees in Congo but the family plans to return to their homeland in the near futre. The most important thing that they possess is the mattress shown in this photograph, which all three women, and a small child, sleep on. Mama Jeanne says of it, “We bought it for $85. At the time, the children were all sleeping on a mat on the ground, and we decided to give them something better. Her daughter Joelle says that it’s not only that the mattress helps to keep them warm, but “It’s about the family honor, and a way to be proud. When we are in Angola we will use it if someone comes to visit us. We will not be ashamed to give it to them if they want to sleep”. (Photo by Brian Sokol/Panos Pictures)

Leila (name changed for protection purposes), 9, poses for a portrait in the urban structure where she and her family are taking shelter in Erbil, in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq, on 17 November 2012. Together with her four sisters, mother, father and grandmother, Leila arrived in Erbil five days before this photograph was taken, after fleeing their home in Deir Alzur, Syria. Her family is one of four living in an uninsulated, partially-constructed home; there are about 30 people sharing the cold, draughty space. Leila recalls explosions all around them for days, but the family finally decided to leave Deir Alzur when their neighbours' house was hit, killing everyone inside. The most terrifying thing about the months before they fled, she says, “was the voice of the tanks. It was even more scary than the sound of planes, because I felt like the tanks were coming for me”. In the background throughout the interview with Leila, a television channel from Deir Alzur displayed images of incredibly graphic violence and destruction. When asked what she feels when seeing those images again and again, she replied, “Watching the TV makes me remember Syria and what I saw there. It makes me feel sorry and sad in my heart – but I want to keep it on”. The most important thing Leila was able to bring with her are the jeans she holds in this photograph. “I went shopping with my parents one day and looked for hours without finding anything I liked. But when I saw these, I knew instantly that these were perfect because they have a flower on them, and I love flowers”. She has only worn the jeans three times, all in Syria – twice to wedding parties, and once when she went to visit her grandfather. She says she won't wear them again until she attends another wedding, and she hopes it, too, will be in Syria. (Photo by Brian Sokol/Panos Pictures)

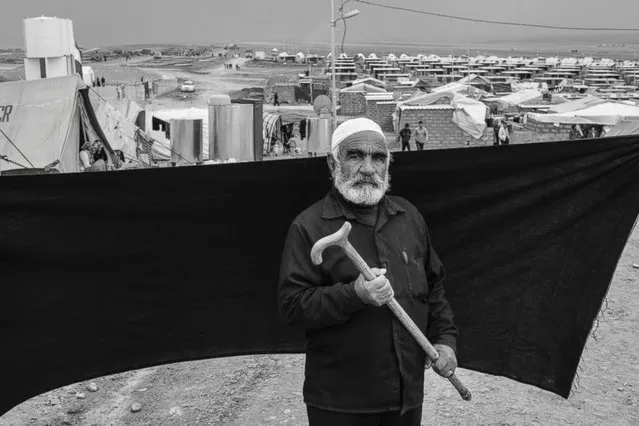

Ahmed (name changed for protection purposes), 70, poses for a portrait in Domiz refugee camp in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq on 14 November 2012. Ahmed fled Syria with his wife and eight of their nine children approximately four months before this photograph was taken, when their family home in Damascus was destroyed in an attack. Together with four other families – 50 people in all – they escaped in the back of an open-topped truck after covering themselves with plastic sheeting. The vehicle set out at midnight and Ahmed says everyone aboard was terrified, fearing that they would not reach safety. Many hours later they arrived in Derik City, where they spent 20 days before continuing on to the Iraqi border. Ahmed's one son who remained behind was killed in late October 2012. Following an explosion, he ran into the street to help an injured friend, only to be killed in a second blast. The most important thing Ahmed was able to bring with him is the cane he holds in this photograph. Without it, he says, he would not have made the two-hour crossing on foot to the Iraqi border. “The only other thing I have left is this finger”, he said. “All I want now is for my family to find a place where they can be safe and stay there forever. Never should we need to flee again”. (Photo by Brian Sokol/Panos Pictures)

Dowla Barik, 22, poses for a portrait in Doro refugee camp, Maban County, South Sudan on August 5th, 2012. Several months before, Dowla and her six children fled from their village of Gabanit in Sudan's Blue Nile State after numerous bombing raids forced them from their home. The most important object that Dowla was able to bring with her is the wooden pole balanced over her shoulder, with which she carried her six children during the 10-day journey from Gabanit to South Sudan. At times, the children were too tired to walk, forcing her to carry two on either side. (Photo by Brian Sokol/Panos Pictures)

Malian refugee Doud Ag Ahmidou, 45, left, poses for a portrait with his family near their shelter in Goudebou refugee camp, Burkina Faso on 10 March, 2013. When Doud felt the bombings hit the village next to his encampment, which made his animals lie to the ground in fear, he knew he had to leave as soon as possible. Before that, they have becoming increasingly worried with the exactions committed by the Malian Army. The most terrifying was when the Malian Army bombed the neighbouring encampment in March, 2012, with airplanes killing a good family friend, with whom Doud had grown up with. The Malian Army mistook the camp for a rebel base. As they lived not far from the encampment that was attacked, him and his family heard when the bombs hit, “they made the entire land tremble”. After the bombing stopped, militias came to finish off the job and kill the survivors, at this moment two of their close family friends were killed in this second round of violence. Doud himself arrived in the encampment a couple of hours later and found the bodies that were still there, some of them with cuts and bruises still fresh from the Malian army. The youngest victim was 14, whom he helped bury. This awoke bad memories of 1994, when their extended family was hit by an aerial bombardment campaign that killed 60 people, including direct family members and family friends. After this event, although he wanted revenge and prayed that “God give him the power to eat his enemies roar”, he decided to leave as he feared for the life and future of his children and wife. The most important thing Doud took on his trip was a Touareg Pillow, which was the first item they decided to bring with them. The pillow has two important significance for them. It is an item that could bring immediate comfort during their flight. Doud explained that during the difficult 6-day flight on a donkey’s back towards Burkina Faso, the pillows brought comfort to his children and his wife at night. “By placing their heads on a pillow they brought from their home made them think of the peaceful nights back in our encampment”. Secondly, as the pillow is made out of traditional touareg material, it represents a direct connection of Doud with his ancestors and his traditions. Others in the portrait: Takua (6 years), Ali Yassir (3 years), Salif Al-Islam (1 year). (Photo by Brian Sokol/Panos Pictures)

18 Sep 2015 15:04:00,

post received

0 comments