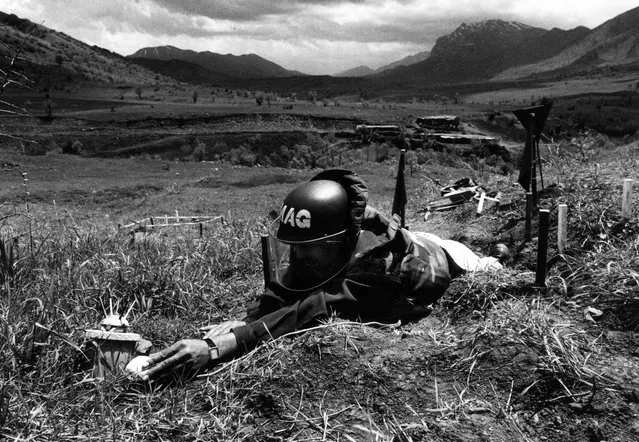

After decades of conflict, Iraq has been left littered with unexploded booby-traps. The Mines Advisory Group has spent 25 years in the country working to destroy and clear some of the millions of pieces of deadly ordnance. These images show members of the organisation at work, and the people whose lives have been touched and transformed by their efforts. Here: The Mines Advisory Group (Mag) has been clearing large areas across northern Iraq since 1992. They have removed and destroyed 167,000 mines, 2m unexploded ordnance and more than 11,000 improvised booby-traps. Here, an explosive is placed beside a fragmentation mine in Choman in 1998. (Photo by Sean Sutton for the Mines Advisory Group/The Guardian)

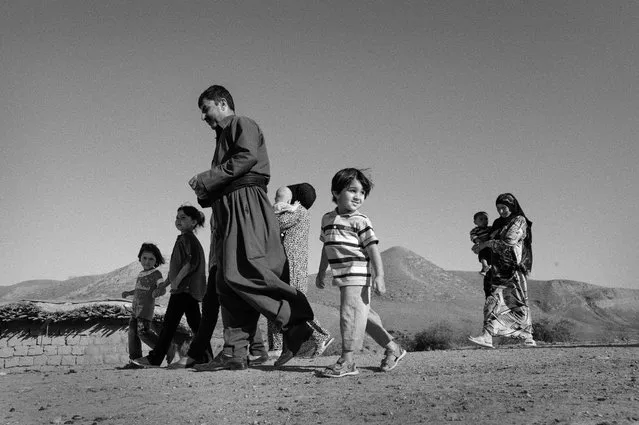

A boy steers his donkey through a minefield in northern Iraq in 2003. Mag has cleared more than 104 sq km of land in the region, allowing people to return to their homes and rebuild their lives. (Photo by Sean Sutton for the Mines Advisory Group/The Guardian)

A deminer carefully carries a 120mm mortar to a demolition site in Iraq in 1998. The global death toll from landmines hit a 10-year high in 2015, with the Landmine Monitor recording 6,461 casualties. The increase was driven by armed conflicts in Libya, Syria, Ukraine and Yemen, together with the improved availability of data. (Photo by Sean Sutton for the Mines Advisory Group/The Guardian)

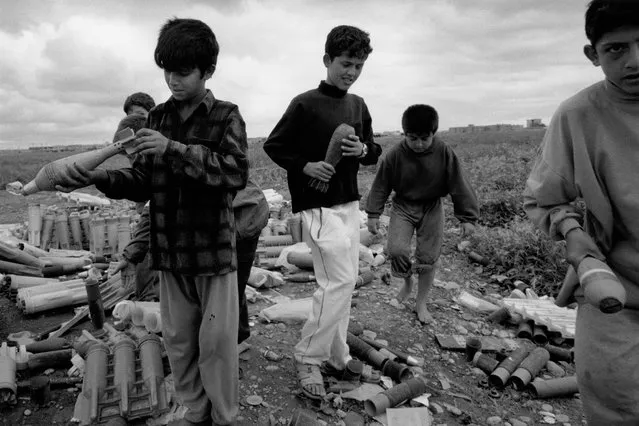

Children are often the casualties of left-behind war ordnance. The day after this photograph was taken in Kirkuk, three of the children pictured died after putting a bomb they had collected into a fire. (Photo by Sean Sutton for the Mines Advisory Group/The Guardian)

Ten-year old Khadab found a cache of munitions in a school in Kirkuk in 2003. He was terribly injured after trying to burn gunpowder and explosives taken from the ordnance. (Photo by Sean Sutton for the Mines Advisory Group/The Guardian)

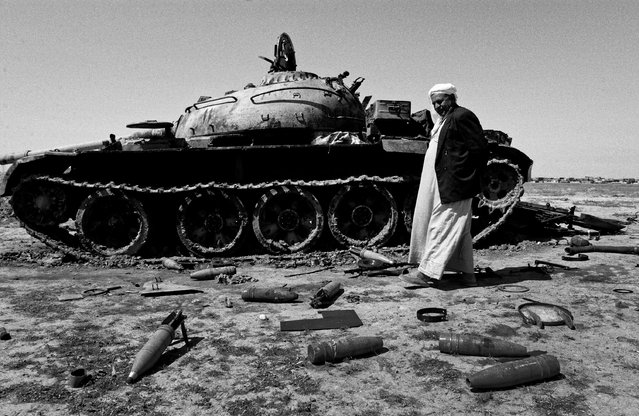

Iraqi children playing on a destroyed tank in 2003, unaware of the explosive danger carpeting the area around them. Their father had been salvaging aluminium from inside the tank. (Photo by Sean Sutton for the Mines Advisory Group/The Guardian)

A man is seen next to a tank outside Kirkuk in 2003. Tanks had been hit by aircraft and abandoned, leaving unexploded ordnance scattered across a wide area. (Photo by Sean Sutton for the Mines Advisory Group/The Guardian)

Ismail Mustafa, seen in 2007. “I was collecting mushrooms on the hill near here. I didn’t see the mine. There was a huge explosion. When I woke up I saw that both my legs were gone; I thought my life was over. My brother and another guy were with me. They made a stretcher from sticks and tied it together with clothing. It took two hours to get off the mountain. ‘My daughter has also been injured. She found a shell and brought it into the house and put it on the fire. She didn’t know what she was doing at the time – she was only three. She is blind and has lost an arm”. (Photo by Sean Sutton for the Mines Advisory Group/The Guardian)

A deminer removing the detonator from the underside of a VS-50 anti-personnel landmine in 2003. (Photo by Sean Sutton for the Mines Advisory Group/The Guardian)

Deminers preparing for work in a minefield near Kurmal close to the Iranian border in 2010. Large areas of northern Iraq were mined during the Iran-Iraq war. Mag trains men and women to take up the dangerous work. (Photo by Sean Sutton for the Mines Advisory Group/The Guardian)

Mag teams cleared 13 minefields around the village of Pirijan, northern Iraq, in 2014 and so far eight families have returned. Before clearance, two people lost a leg and three people lost their hands in explosions. Head man Shakr Ahmad said demining work had ‘given us our soul and given us life again’. When Shakr returned to the village in 2003 he kept losing his sheep to landmines. But demining has changed the fortunes of the village dramatically. “Now I have 550 sheep and grow wheat and vegetables. Before we could barely survive. All the families here are in a good situation now and we have nothing to fear”. (Photo by Sean Sutton for the Mines Advisory Group/The Guardian)

A deminer stops working as local children pass by en route to school. (Photo by Sean Sutton for the Mines Advisory Group/The Guardian)

After inserting a pin to stop the mine from initiating, team leader Salahaddin Mahmad carefully lifts the crown of a Valmara bounding fragmentation mine in farmland in 2010. This mine has a killing range of 30 metres. (Photo by Sean Sutton for the Mines Advisory Group/The Guardian)

Sharabun Aziz, a Mag deminer: “My job is amazing. I am a woman and I am working like a man. That is quite normal in my community, we don’t really differentiate between men and women. A woman is strong. I feel so good about the work we do – we are making a massive contribution and we work together like sisters”. (Photo by Sean Sutton for the Mines Advisory Group/The Guardian)

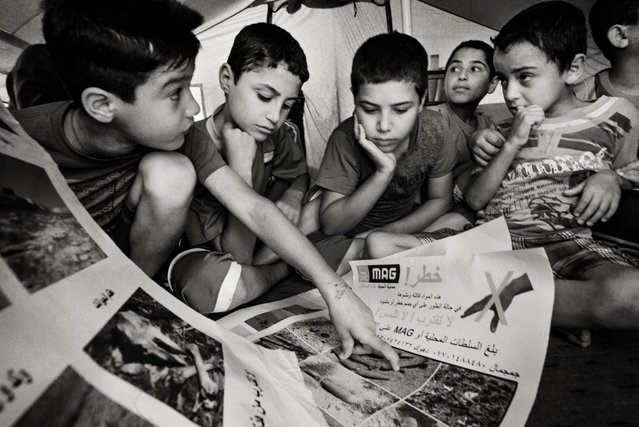

A Mag risk education session for children is held at Derabund refugee camp in Erbil in 2014. (Photo by Sean Sutton for the Mines Advisory Group/The Guardian)

Mag technical staff conduct a visual search at Derabun, Dohuk in 2014. Up to this point they had found and removed 176 live unexploded ordnance and 386 unfused explosive items. (Photo by Sean Sutton for the Mines Advisory Group/The Guardian)

Children injured in a landmine explosion in Iraq in 2016. Ali lost his left eye: “We were playing football and we found something metallic, it was a white colour. We didn’t know what it was and we played with it and tried to open it. It exploded”. (Photo by Sean Sutton for the Mines Advisory Group/The Guardian)

Distraught families with children injured in a landmine blast as they fled the front line are seen in Gogjali, east of Mosul, in 2016. (Photo by Sean Sutton for the Mines Advisory Group/The Guardian)

Ibrahim Abu Farham, a shepherd, in Moshrefa village in 2016, next to land ploughed for the first time since the war. All of the fields pictured were cleared by Mag teams. “My 19 year-old cousin was trying to clear the landmines here to stop his sheep from blowing up. He set one off and was killed. Nine people have been killed here by these landmines in the village. It is a tragedy”. (Photo by Sean Sutton for the Mines Advisory Group/The Guardian)

Controlled demolition of landmines and ordnance, in Bashiqa this year. Mag teams destroy what has been found and defused once a week. (Photo by Sean Sutton for the Mines Advisory Group/The Guardian)

08 Sep 2017 09:33:00,

post received

0 comments