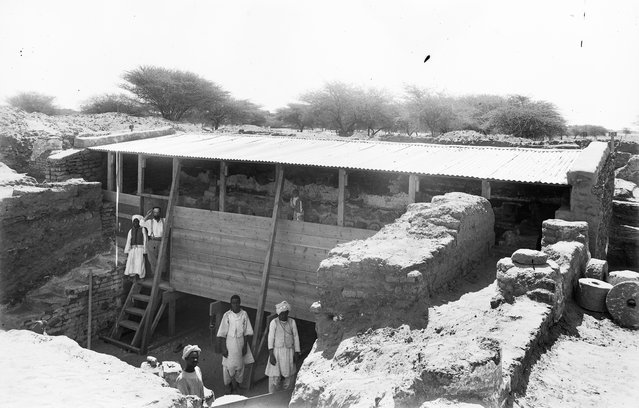

The city of Meroë laid undiscovered for two millennia before British archaeologist John Garstang excavated it in the early 20th century. Garstang took the radical decision to document his discoveries with photography – and immortalised an ancient world. “Meroë: Africa’s Forgotten Empire” is being shown until 14 September at Garstang Museum of Archaeology, Liverpool. Here: A shelter built to protect sculptures at the royal baths. John Garstang can be seen standing on a ladder at the entrance with a workman, 1912. (Photo by Garstang Museum of Archaeology)

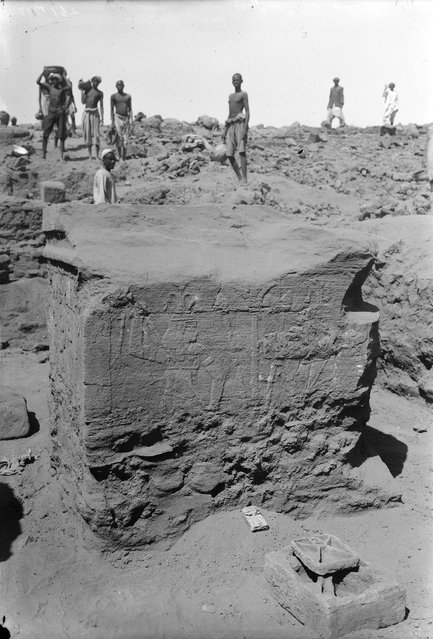

Garstang was born in Blackburn in 1876, and got a scholarship to study maths at Oxford University. During holidays he indulged a newfound interest in archaeology, excavating Roman sites in Britain. Here: High altar with relief featuring Hapi the Nile god, found in the central sanctuary of the Temple of Amun, 1912. (Photo by Garstang Museum of Archaeology)

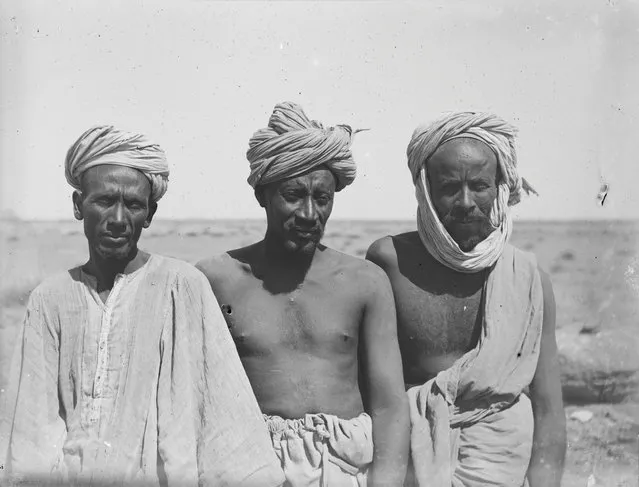

Following later excavations in Egyptian sites like Reqaqnah, Beit Khallaf and Abydos, Garstang came to Meroë, an ancient city on the banks of the Nile situated in what is now Sudan. Here: Three of Garstang’s Sudanese excavators, 1910. (Photo by Garstang Museum of Archaeology)

Meroë had lain undisturbed for 2,000 years before Garstang began his excavations. Here: Decorated column capital, found at the Amun temple, 1910. (Photo by Garstang Museum of Archaeology)

Committees of wealthy individuals would fund the excavations, in exchange for being able to keep objects found by Garstang and his team. Here: Female statue discovered in the palace, after restoration. A local workman holds a backcloth, 1912. (Photo by Garstang Museum of Archaeology)

Remarkable discoveries were made, like the decapitated head of a bronze statue of Roman emperor Augustus, sacked from a raid on Roman garrisons further north in Egypt. Here: A group visiting the excavations at Meroë, including (from left) Midwinter Bey, director of Sudan Railways; Lord Kitchener; General Sir Francis Reginald Wingate, Sirdar of the Egyptian Army; Professor Archibald Sayce; John Garstang; and Lady Catherine Wingate, 1911. (Photo by Garstang Museum of Archaeology)

The head was buried underneath a doorway to a building thought to be a victory monument or temple – in walking over the head, Meroites would effectively reiterate their victory. The piece is now owned by the British Museum. Here: Traditional east African Tukul house, near the site of Meroë, 1910. (Photo by Garstang Museum of Archaeology)

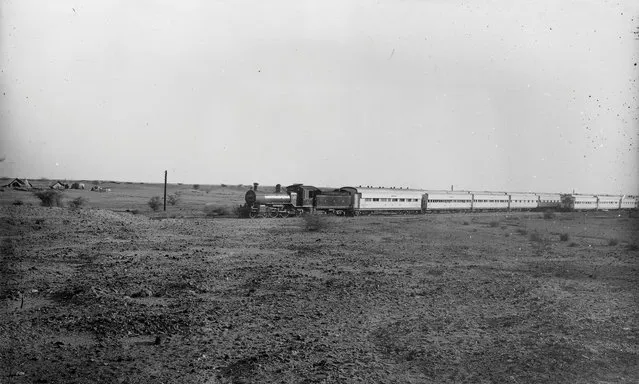

Garstang also discovered brightly coloured frescoes, though these were destroyed a few years later after the building he stored them in was damaged in a storm. Here: A steam train passing Garstang’s camp at Meroë, visible in the background, 1911. (Photo by Garstang Museum of Archaeology)

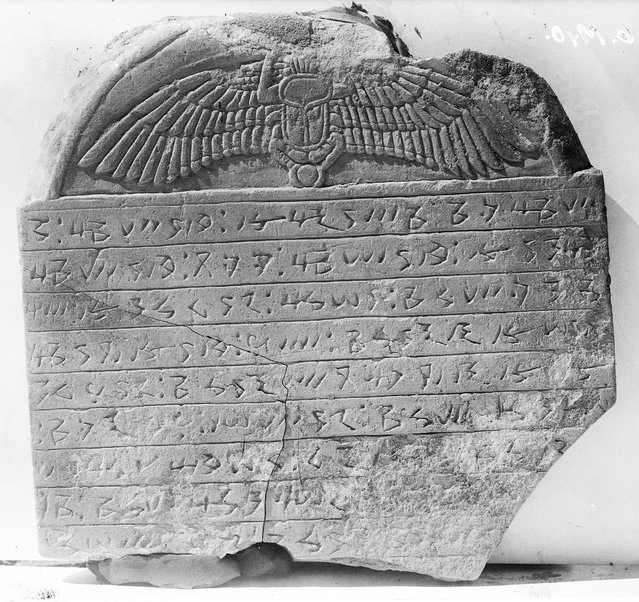

Lion imagery was prevalent, including in a temple adored with the lion headed god Apedemak. Here: Upper fragment of a stele (inscribed stone) in Meroitic script, found at the lion temple, 1910. (Photo by Garstang Museum of Archaeology)

The Garstang Museum in Liverpool has recently 3D-printed copies of various artefacts found at Meroë. Here: Garstang and his wife Marie examining statue fragments in the tank at the “Royal Baths”, 1913. (Photo by Garstang Museum of Archaeology)

Following his Egyptian work, Garstang went on to make major excavations in Israel, heading Jerusalem’s British School of Archaeology, and Turkey, the latter completed after the second world war halted his progress. He then founded the British Institute of Archeology in Ankara. Here: Aerial railway in use at the site. Widnes and Port Said can be seen written on the box. (Photo by Garstang Museum of Archaeology)

15 Jun 2016 14:49:00,

post received

0 comments