Easter Bunny. “This was taken in the 1970s, when I was in love with New York. The place was full of soul back then: there was life on the streets, eccentric characters on every corner, millions of people with colourful stories to tell. I mean it’s not every day you go out and see an Easter bunny on a tricycle, is it? People came to New York to be New Yorkers, not just because they got a job in the city. It was so alive. I would hang my camera around my neck and hit the streets, knowing that some quirky character would soon come my way. And there I was walking through Greenwich Village when this charming elderly lady rode past, full of smiles. She was happy that I noticed her. I remember thinking what lovely spirit she had. There is an innocence about her that I still adore – an older woman with a sense of fun, enjoying her life and making everyone around her happy. Nowadays, when I look at this photo, I just see a New York that has lost its heart and soul. The city has became all about real estate and money. It used to be about neighbourhoods, each one like a small town, with its own flavour and personality. Greenwich Village was the bohemian area, with bars open late and jazz. I’m heartbroken to think it’s gone”... (Photo by Jill Freedman/Steven Kasher Gallery)

Nineties here we come … from left, Naomi Campbell, Linda Evangelista, Tatjana Patitz, Christy Turlington and Cindy Crawford. “Liz Tilberis, the editor of British Vogue, asked me to do a shoot. “You have to do the January 1990 cover”, she said. “You’re the one”. She wanted something that would preview the decade to come. My reaction was: “Oh my God, who could that be? You can’t hang the next decade on one face. It won’t work”. But I knew what would. This was the result. People always say this shot, this cover, was the birth of the supermodels. (Photo by Peter Lindbergh/The Guardian)

“A very delicate person, beneath the flamboyance”. Jasper, Ladbroke Grove, 1977. “In the 1970s, Australia was rather cut off. I’d always wanted to live abroad, so I moved to Rome and then London. I was an art historian, but started studying photography part-time. I was interested in the demi-monde culture and began mixing in all sorts of circles. Jasper was a rather wonderful character. He was from Sydney, but he was living downstairs from me in Ladbroke Grove, in a flat rented to some gay friends. It was fairly eclectic. Jasper was always playing around with clothes and makeup. If he was looking particularly wonderful, I might get out my lights and take a shot. Or he might put makeup on me. He wasn’t always in drag, but he was permanently in diva mode, dependably louche, funny and naughty. I think all that comes across in the image. He was actually a very delicate person, though, beneath the wit and flamboyance. Jasper floated through London all too briefly. His real name was Peter MacMahon, but to us he was only ever Jasper Havoc, an alter ego he’d created while part of a transvestite troupe called Sylvia and the Synthetics. They were legendary in Sydney gay culture. On this day, we’d been taking some pictures inside and had gone out into the streets to fool around some more. Jasper was wearing a corset and fishnets ensemble, with other bits and pieces, and we joked about him being trashy as he lay in the skip. We just took the shot for ourselves. It wasn’t done with any publication in mind, or anything else. This was way before the internet and people didn’t share images. If you dressed up, it was just for that moment”. (Photo by Jane England)

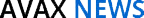

Mercenary, El Salvador. “I came across this guy during the civil war in El Salvador in the 1980s. He was one of a gang of mercenaries known as the Death Squad. We were in a rural backwater called Suchitoto, which at the time could best be described as a one-donkey town, and he was sitting in the local cafe having eaten his lunch, his revolver casually placed in front of him. I bought him a beer and, as he raised the bottle, managed to get three shots in before he went ballistic. He was swearing and called his friends with rifles over and pushed me about. I don’t know what would have happened if they’d realised I’d shot off some frames already. I realised I’d taken a big risk, but I didn’t think about it at the time. I quickly ordered more beers, hoping to calm them down, and then just left”. (Photo by Derek Hudson)

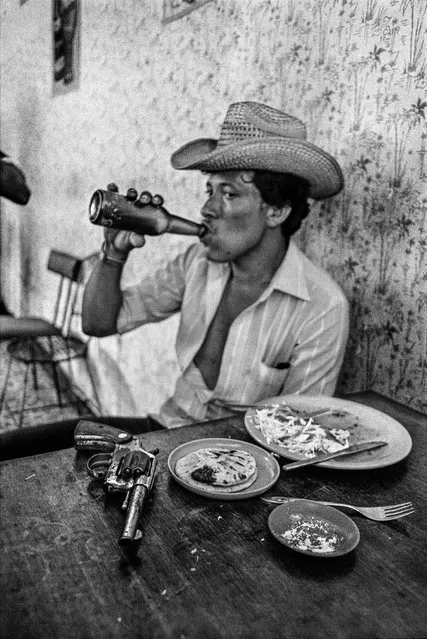

“I came across this girl in the Oxford University parks, lying in the summer sun reading a book. It was in the late-60s, not a laptop in sight. It was surprising to find an unshaven armpit, almost as shocking as pubic hair. It’s from The Oxford Pictures, my first photographic essay. It was very much a young man’s vision: anxiety, desire and sexual guilt run right through it, maybe because of my strict upbringing with Sunday school lessons and Christian teaching. It might have been the swinging 60s, with lots of photos in the papers of girls in miniskirts and Mick Jagger in a white dress, but plenty of people felt they were missing out – that this sexual revolution was somewhere else, out of reach. We felt the barriers rather than the freedoms. So I looked for visual moments that reflected my sense of being an outsider: isolated figures beside the river, or sitting on a park bench”. (Photo by Paddy Summerfield)

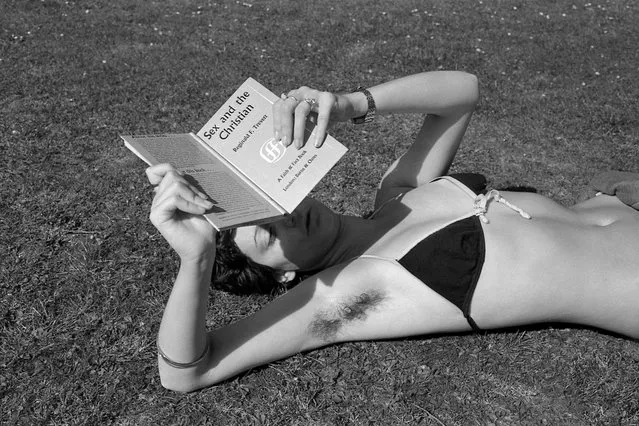

“It feels prophetic” … the shot Morris took in the Black House in 1969. “When I was 14, I used to go to a place in London called the Black House, an organisation run by Michael X, who had been a henchman for a slum landlord. When he came round, if you didn’t pay, you got hurt. But then he switched and tried to become England’s answer to Malcolm X – except he was nothing like him. He got some funding, though, and some donations from John Lennon and Yoko Ono, to create a community centre for young black kids. It was a very militant organisation, constantly being raided by the police, who thought there were lots of drugs and guns on the premises. It eventually closed because of the pressure. Michael then went to Trinidad and set up a commune. He went crazy and killed two people there, including the daughter of a British MP, and was hanged. The Black House had a library, a games room and a rehearsal room. We congregated there, those of us who wanted to find out more about ourselves. It was quite a big building, a warren of rooms and basements. You’d turn a corner and stumble across some secret meeting you shouldn’t be a part of. While walking around one day, I came across this kid and took some shots. I don’t remember who it was, but there were no questions, no who, what, where. I knew immediately it would make a great photograph. I was quite frightened – the way he was handling the gun, the way he portrayed himself, he had a sense of purpose. He was about 10”. (Photo by Dennis Morris)

General Boris V. at his house in Star City, Russia, 2007. “Star City is a self-contained city for cosmonauts about an hour from Moscow. Astronauts still come from all over the world to get trained there. It might look dated but, underneath, the important stuff is all working. As well as a training centre, it has a launch site, a technical department, a school, and a hospital – everything really. During the cold war, when there was a lot of money going into the space race, it was an important place. That’s not so much the case now. We are all awed by space – and, although there is something old-fashioned, even funny, about this image, it is still noble. The subject’s name is General Boris V. and I took his portrait back in 2007. Originally, the Yuri Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Centre had agreed to let me shoot on their premises, but when I got there they asked for money. In Russia, to get anything done, you need either money or vodka – so we went to the cafeteria and started drinking. After an hour or two, Boris suggested we take the spacesuit to his house and just do it there. It took eight months to set up the visit to Star City – and just half an hour to get the shot. He’s only had that suit on for less than half an hour, but it was so heavy he could hardly cope. You can tell he’s struggling – his expression is 100% natural. Taking the picture at his house made it so much more interesting. I love the contrast between this futuristic idea of space and the old-fashioned wallpaper. The bit of wood on the right is actually the corner of his son’s bed. (Photo by Vincent Fournier/The Guardian)

“This image is taken from my 24 series, a collection of self-portraits exploring what it’s like growing up with HIV. I was born with the virus – I’ve never known life without it. I wanted to explore how this can feel, how it can look, how living with HIV has differed from what I expected. All the photos are glamorous, very cinematic and theatrical, as if I’m on stage or in a film. It’s a kind of re-imagination: what my life might have been like had things been different. I took the shot in 2015, but it had been in my head for a long time. I’m with my doctor, whose surgery I have visited regularly since the age of four. He checks my blood and monitors my numbers to make sure I’m healthy. The photo shows what I see in my head when I go for check-ups. I suppose it’s a kind of fantasy. The dress is the one I wore to my school prom. The colour, the glamour, the juxtaposition – there’s an element of fashion photography, something that has always inspired me”. (Photo by Kia LaBeija)

Hanging dogs; South of Tambo, Queensland, Australia, 2014. “The farmers hang up the wild dogs to show the public how serious the situation is (wild dogs attacking sheep). It’s on the side of the road and it’s very public”. (Photo by Matthew Abbott)

Passion and persecution: Bangladesh's outcasts. Before he began photographing the LGBT community in his native Bangladesh towards the end of 2008, Gazi Nafis Ahmed spent a year in their midst without taking a single shot. “I was content just to hang around and socialise”,” he says. “Though my work is ooted in traditional documentary, I cannot photograph people I cannot be friends with. So it is important for me to first create a space for us to be comfortable. The work flows from that”. The result is Inner Face, an insider view of a community that is relatively invisible in Bangladesh’s conservative, patriarchal society. In series of black and white photographs, Ahmed eschews documentary detachment, favouring a more intimate – often playful – kind of collaboration. “I want my subjects to express themselves freely”, he says, “and that involves a huge level of trust on their part”. (Photo by Gazi Nafis Ahmed)

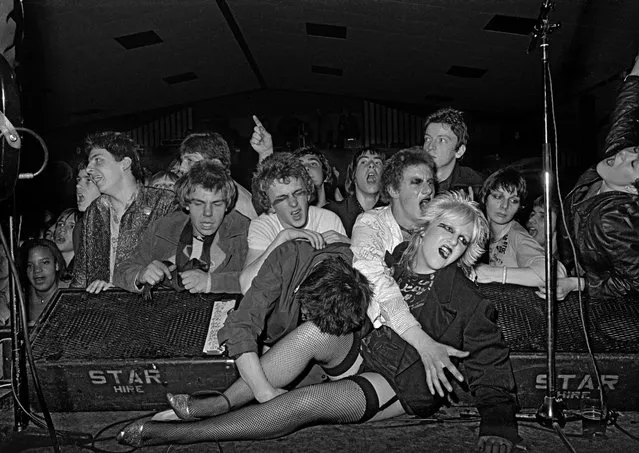

A stagecrashing punk in Norfolk, East Anglia. “I took this photograph at a Rock Against Racism gig in 1979. The Ruts were playing the West Runton Pavilion in Cromer, and it was rammed and really hot, but also really exciting. Everyone was pogoing and jumping up and down with their fists in the air – it was mayhem. I was near the front when I saw the girl climb up on to the stage and take up that reclining pose between two monitors. It was one of those adrenaline-driven moments when nothing matters apart from getting the shot. So I climbed over everyone’s heads and dragged myself on to the stage in front of the lead singer, Michael Owen. I had my two Nikons around my neck and a big old Norman flash and it just went pop. A second later I was in the air and then on my back in the middle of the audience. The bouncer had thrown me off the stage. I still have those cameras and one of them has a big dent from that night”. (Photo by Syd Shelton)

Tête-à-Tête, Bavaria, 2015. One of the images from Ellen von Unwerth’s “Heimat”. Photograph: Ellen von Unwerth can’t stop laughing. The German photographer, 63, is bouncing around the Taschen gallery in West Hollywood in her sneakers, attempting to talk through the images from her latest exhibition and art book, “Heimat”. “So heimat means Fatherland or Motherland or where you were born and where your roots are”, she tells me. “Bavaria is not my heimat, but we wanted to make a parody of the whole Bavarian thing”. The whole Bavarian thing, apparently, involves supermodels frolicking nude in Alpine meadows, performing suggestive acts with sausages, udders and holy virgins, sledging topless, spanking one another in dirndls and generally enjoying the fecundity and vigour for which the southern German slopes are celebrated. “Oh, ja, it’s very sexual there, even the clothes they push up the bosoms and there are lots and lots of sausages, ha ha ha”, she explains. “But you see so many images that are dark and depressing at the moment. All these sad women being sad! So I figured, let’s show girls having fun and enjoying life”. (Photo by Ellen von Unwerth)

26 Jun 2017 09:04:00,

post received

0 comments