Sacred no more: Mr Amakaki (left) gets ready to babysit Sakura, a macaque owned by his neighbor Kaoru Amagai, in Ōta-shi, Gunma, central Japan, October 2, 2017. In recent years, the Japanese macaque, best known as the snow monkey, has become habituated to humans. As the range of the macaque habitat expands from mountain areas to subalpine and lowland regions, the animals have lost their fear, have taken to raiding crops, and are often seen as pests. Despite macaques being officially protected in Japan since 1947, some local laws allow them to be tamed and trained for the entertainment industry. Once considered sacred mediators between gods and humans, monkeys in Japan also came to be seen as representing dislikable humans, deserving of ridicule. Commercial entertainment involving monkeys has existed in Japan for over 1,000 years. (Photo by Jasper Doest/World Press Photo)

Environment – stories, first prize. A man carries a huge bag of bottles collected for recycling at the Olusosun landfill site in Lagos, Nigeria. (Photo by Kadir Van Lohuizen/Noor Images/World Press Photo)

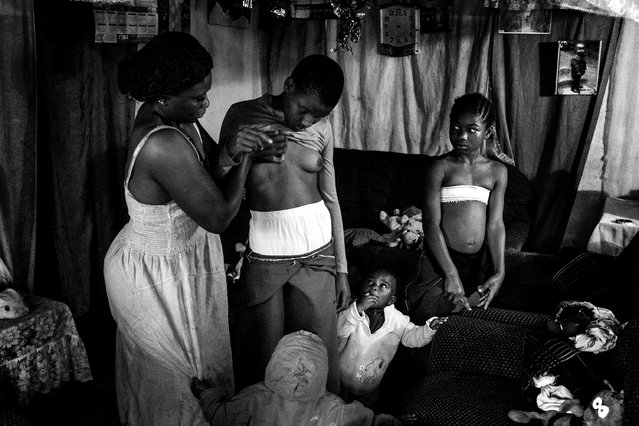

Contemporary issues – stories, first prize. A handout photo made available by World Press Photo (WPP) organization shows a picture of photographer Heba Khamis that wins the 1st prize of the “Contemporary Issues – Stories” category in the World Press Photo 2018 Contest as it was announced by World Press Photo on 12 April 2018. The picture from a story shows Veronica, 28, as she massages the breasts of her 10-year-old daughter, Michelle, as her other children watch in Bafoussam, Cameroon, 07 November 2016. Veronica started to iron Michelle's breasts seven months before this image was taken. Her older daughter, not pictured, refused to have her breasts ironed and became pregnant at 14 years old. (Photo by Heba Khamis/EPA/EFE/World Press Photo)

Peace football club: Members of the Colombian army play a friendly match with a FARC team in Vegaez, Antioquia, Colombia, September 16, 2017. Guerrillas of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), having laid down weapons after more than 50 years of conflict, have moved from jungle camps to ‘transitional zones’ across the country, to demobilize and begin the return to civilian life. Many are taking part in football matches with teams made up of members of the Colombian military, as well as victims of the conflict. The plan is for the best players from transitional-zone teams to form La Paz FC (Peace FC) football team. (Photo by Juan D. Arredondo/World Press Photo)

Venezuela crisis: José Víctor Salazar Balza (28) catches fire amid violent clashes with riot police during a protest against President Nicolás Maduro, in Caracas, Venezuela, May 3, 2017. President Maduro had announced plans to revise Venezuela’s democratic system by forming a constituent assembly to replace the opposition-led National Assembly, in effect consolidating legislative powers for himself. Opposition leaders called for mass protests to demand early presidential elections. Clashes between protesters and the Venezuelan national guard broke out on 3 May, with protesters (many of whom wore hoods, masks or gas masks) lighting fires and hurling stones. Salazar was set alight when the gas tank of a motorbike exploded. He survived the incident with first- and second-degree burns. (Photo by Ronaldo Schemidt/AFP Photo/World Press Photo)

More Than a Woman: Dr Suporn Watanyusakul shows patient Olivia Thomas her new v*gina after gender reassignment surgery at a hospital in Chonburi, near Bangkok, Thailand, February 3, 2017. Thailand leads the world as a medical tourism destination, with gender-affirming surgery forming a strong niche. Treatment can be considerably cheaper than in other countries around the world, and the large numbers of patients mean that surgeons become highly experienced. The use of new technologies and procedures is also often given as a reason for Thailand’s popularity among people seeking treatment for gender dysphoria. (Photo by Giulio Di Sturco/World Press Photo)

Kid jockeys: Young jockeys compete in a Maen Jaran horse race, on Sumbawa Island, Indonesia, September 17, 2017. Child jockeys ride bareback, barefoot and with little protective gear, on small horses, during Maen Jaran horse races, on Sumbawa Island, Indonesia. Maen Jaran is a tradition passed on from generation to generation. Once a pastime to celebrate a good harvest, horse racing was transformed into a spectator sport on Sumbawa by the Dutch in the 20th century, to entertain officials. The boys, aged between five and ten, mount their small steeds five to six times a day, reaching speeds of up to 80 kilometers per hour. Winners receive cash prizes, and participants earn €3.50 to €7 per mount. (Photo by Alain Schroeder/Reporters/World Press Photo)

Environment, first prize stories: Kadir van Lohuizen, the Netherlands. Wasteland: People wait to sort through waste for recyclable and saleable material, as a garbage truck arrives at the Olusosun landfill, in Lagos, Nigeria, January 21, 2017. Humans are producing more waste than ever before. According to research by the World Bank, the world generates 3.5 million tonnes of solid waste a day, ten times the amount of a century ago. Rising population numbers and increasing economic prosperity fuel the growth, and as countries become richer, the composition of their waste changes to include more packaging, electronic components and broken appliances, and less organic matter. Landfills and waste dumps are filling up, and the World Economic Forum reports that by 2050 there will be so much plastic floating in the world’s oceans that it will outweigh the fish. A documentation of waste management systems in metropolises across the world investigates how different societies manage – or mismanage – their waste. (Photo by Kadir van Lohuizen/NOOR Images/World Press Photo)

Attack of the zombie mouse: A juvenile gray-headed albatross on Marion Island, South African Antarctic Territory, is left injured after an attack by mice from an invasive species that has begun to feed on living albatross chicks and juveniles, May 1, 2017. Mice were introduced to the island by sealers in the 1800s and co-existed with the birds for almost 200 years. In 1991, South Africa eradicated feral cats from Marion Island, but a subsequent plan to do the same to the mouse population failed to materialize. An expanding population and declining food sources led the abnormally large mice to attack albatrosses and burrowing petrels. An environmental officer has now been appointed to monitor the mouse population and conduct large-scale poison bait trials. (Photo by Thomas P. Peschak/World Press Photo)

White Rage – USA: Tommy Kinder poses with his rifle in his home in Fork Creek, W.V., September 29, 2017. He is a patriot and proud of his country, but is afraid U.S. is being destroyed by unemployment and drugs. Degrees of rage in three US states: a journey made in the weeks after the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia. The rally was the first gathering of far-right groups from all over the country in decades, held in part to demonstrate opposition to the removal of the statue of Confederate general Robert E. Lee. The photographer travelled through Virginia, West Virginia and Maryland meeting a range of people, from extreme right activists to patriots and those angry at the way the US is governed, in an attempt to understand why white anger has risen to the surface. (Photo by Espen Rasmussen/Panos Pictures/VG/World Press Photo)

General news – stories, first prize. Nadhira Aziz watches as Iraqi civil defence workers recover the bodies of her sister and niece from her house in the city of Mosul, where they were killed by an airstrike in June. By the end of the battle for Mosul, more than 9,000 civilians were reported to have been killed. (Photo by Ivor Prickett/The New York Times/World Press Photo)

Rohingya Refugees Flee Into Bangladesh: A Rohingya refugee is helped from a boat as she arrives at Shah Porir Dwip, near Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh, October 1, 2017. Attacks on the villages of Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar, and the burning of their homes, led to hundreds of thousands of refugees fleeing into Bangladesh on foot or by boat. Many died in the attempt. According to UNICEF, more than half of those fleeing were children. In Bangladesh, refugees were housed in existing camps and makeshift settlements. Conditions became critical; basic services came under severe pressure and, according to a Médecins Sans Frontières physician based there, most people lacked clean water, shelter and sanitation, bringing the threat of disease. (Photo by Kevin Frayer/Getty Images//World Press Photo)

Ich bin waldviertel: Ich Bin Waldviertel: Martin and Christian (brothers who spend their summer holidays in Waldviertel) watch Alena in one of the barns, August 6, 2014. Hannah and Alena are two sisters who live in Merkenbrechts, a bioenergy village of around 170 inhabitants in Waldviertel, an isolated rural area of Austria, near the Czech border. The girls have two older brothers, but spend much of their time together in a carefree life, swimming, playing outdoors and engrossed in games around the house. A bioenergy village is one which produces most of its own energy needs from local biomass and other renewable sources. The photographer has been photographing Hannah and Alena since 2012. She visits them for a few weeks, usually at summertime, every year, watching them growing up and spending time together. (Photo by Carla Kogelman//World Press Photo)

Earth kiln: Two brothers live in a traditional yaodong (“kiln cave”), carved into a hillside on the Loess Plateau in central China. The earth-lined walls have good insulating properties, enabling residents to survive cold winters, November 11, 2017. The yaodong is one of the earliest housing types in China, dating back more than 2,000 years. The Loess Plateau in the upper and middle reaches of the Yellow River, is approximately the size of France.The loess soil – fine, mineral-rich, wind-blown silt, accumulated over centuries – is hundreds of meters thick in some places, and the numbers of yaodong run into millions. The loess not only keeps the dwellings warm in winter, but also cool in summer. The brothers, who are both unmarried, have lived in this yaodong for most of their lives. (Photo by Li Huaifeng/World Press Photo)

Demonstrator catches fire: Víctor Salazar catches fire after a motorcycle explodes, during a street protest is Caracas, Venezuela, May 3, 2017. José Víctor Salazar Balza (28) caught fire after the gas tank on a motorcycle exploded, during a protest against the Venezuelan president, Nicolás Maduro, in Caracas. Violent clashes had broken out between demonstrators and the national guard. The motorcycle, belonging to a member of the national guard, was apparently being destroyed by protesters. Accounts of the incident differ, but some say that an object thrown by protesters caused the gas tank to explode. Further reports maintain that Salazar’s clothing caught fire so readily because he was doused in petrol either by a bomb he was carrying, or that of a fellow protestor. Salazar suffered severe burns to more than 70% of his body, but survived the incident. (Photo by Juan Barreto/Agence France-Presse/World Press Photo)

Car attack: People are thrown into the air as a car plows into a group of protesters demonstrating against a Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Va., August 12, 2017. The white nationalist rally, opposing city plans to remove a statue of Confederate icon General Robert E. Lee, attracted counter-protests. James Alex Fields Jr drove his car at high speed into a sedan, propelling it and a minivan into a group of anti-racist protesters, killing Heather Heyer (32) and injuring a further 19 people. Fields fled the scene in his own vehicle, but was stopped by Charlottesville police and later charged with murder. (Photo by Ryan M. Kelly/The Daily Progress/World Press Photo)

Royal Shrovetide football: Members of opposing teams, the Up’ards and Down’ards, grapple for the ball during the historic, annual Royal Shrovetide Football Match in Ashbourne, Derbyshire, UK, February 28, 2017. The game is played between hundreds of participants in two eight-hour periods on Shrove Tuesday and Ash Wednesday (the day preceding and the day marking the start of Christian Lent). The two teams are determined by which side of the River Henmore players are born: Up’ards are from north of the river; Down’ards, south. Players score goals by tapping the ball three times on millstones set into pillars three miles apart. There are very few rules apart from an historic stipulation that players may not murder their opponents, and the more contemporary requirement that the ball must not be transported in bags, rucksacks, or motorized vehicles. Royal Shrovetide Football is believed to have been played in Ashbourne since the 17th century. (Photo by Oliver Scarff/Agence France-Presse/World Press Photo)

The battle for Mosul: Iraqi Special Forces soldiers survey the aftermath of an attack by an ISIS suicide car bomber, who managed to reach their lines in the Andalus neighborhood, one of the last areas to be liberated in eastern Mosul, January 16, 2017. Iraqi Special Forces soldiers survey the aftermath of an attack by an ISIS suicide car bomber, who managed to reach their lines in the Andalus neighborhood, one of the last areas to be liberated in eastern Mosul. On 10 July 2017, after months of fighting, the Iraqi government declared the city of Mosul fully liberated from ISIS, although fierce fighting continued in pockets of the city. Mosul had fallen to ISIS three years earlier, and the battle to retake it had begun in October 2016. In effect, the reconquering of Mosul comprised two parts: the battle for the eastern half of the city, and that for the west, across the Tigris River. East Mosul was recaptured by the end of January 2017, but the offensive on west Mosul, particularly the densely built-up Old City, proved more difficult. Large areas of the city were left in ruins, and huge numbers of civilians were caught in the crossfire as battle raged. A United Nations report gives an absolute minimum of 4,194 civilian casualties during the conflict, with other sources putting the figure much higher. The Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights pointed to extensive use of civilians as human shields, with ISIS fighters attempting to use the presence of civilian hostages to make certain areas immune from military operations. After months of being trapped in the last remaining ISIS-held areas of the city, the people in west Mosul were severely short of food and water. Those who chose to remain in the city rather than go to one of the many camps for displaced people, initially relied on aid in order to survive. (Photo by Ivor Prickett for The New York Times/World Press Photo)

Finding Freedom in the Water: A young woman learns to float, in the Indian Ocean, off Nungwi, Zanzibar, November 24, 2016. Traditionally, girls in the Zanzibar Archipelago are discouraged from learning how to swim, largely because of the strictures of a conservative Islamic culture and the absence of modest swimwear. But in villages on the northern tip of Zanzibar, the Panje Project (panje translates as ‘big fish’) is providing opportunities for local women and girls to learn swimming skills in full-length swimsuits, so that they can enter the water without compromising their cultural or religious beliefs. (Photo by Anna Boyiazis/World Press Photo)

Flying fish in motion: A flying fish swims below the surface in the Gulf Stream late at night, offshore from Palm Beach, Fla., August 18, 2017. Moving its tail fin up to 70 times per second, a flying fish can reach an underwater speed of nearly 60 kilometers per hour. Angling itself upwards, it then breaks the surface while still propelling itself along by rapidly beating its tail underwater, before taking to the air and gliding – successfully escaping predators such as tuna, marlin and swordfish. (Photo by Michael Patrick O'Neill/World Press Photo)

Mideast crisis Iraq Mosul: An Iraqi Special Forces soldier some moments after shooting dead a suspected suicide bomber, during the offensive to retake Mosul, March 3, 2017. The battle to reclaim Mosul from ISIS began in October 2016 and lasted until July 2017, with fighting against pockets of ISIS militants continuing in some quarters of the city even beyond that date. The use of suicide bombers was a common tactic by the militants. (Photo by Goran Tomasevic/Reuters/World Press Photo)

Hunger Solutions: Plant scientist Henk Kalkman checks tomatoes at a facility that tests combinations of light intensity, spectrum and exposures at the Delphy Improvement Centre in Bleiswijk, the Netherlands, October 17, 2016. The planet must produce more food in the next four decades than all farmers in history have harvested over the past 8,000 years. Small and densely populated, the Netherlands lacks conventional sources for large-scale agriculture but, mainly through innovative agricultural practice, has become the globe’s second largest exporter of food as measured by value. It is beaten only by the USA, which has 270 times its landmass. Since 2000, Dutch farmers have dramatically decreased dependency on water for key crops, as well as substantially cutting the use of chemical pesticides and antibiotics. Much of the research behind this takes place at Wageningen University and Research (WUR), widely regarded as the world’s top agricultural research institution. WUR is the nodal point of “Food Valley”, an expansive cluster of agricultural technology start-ups and experimental farms that point to possible solutions to the globe’s hunger crisis. (Photo by Luca Locatelli for National Geographic/World Press Photo)

Manal, war portraits: Manal (11), a victim of a missile explosion in Kirkuk, Iraq, wears a mask for several hours a day to protect her face, following extensive plastic surgery at the Médecins Sans Frontières Reconstructive Surgery Program, Al-Mowasah Hospital, Amman, Jordan,July 10, 2017. Children and adults from Yemen, Iraq, Syria and Gaza who have been badly injured by bombs, car explosions or other accidents live in the hospital with a relative or friend. Manal, who was displaced along with her mother and two brothers, endured severe burns to her face and arms. She had no surgery before coming to Jordan and had difficulty in closing her right eye. After many plastic surgery operations, she now wears her mask for several hours a day, primarily to protect her skin from the light. Manal has many friends at the hospital, and loves drawing and telling stories, as well as the many organized activities for children. (Photo by Alessio Mamo/Redux Pictures/World Press Photo)

Boko Haram strapped suicide bombs to them. Somehow these teenage girls survived: Aisha, aged 14, September 21, 2017. Portraits of girls kidnapped by Boko Haram militants, taken in Maiduguri, Borno State, Nigeria. The girls were strapped with explosives, and ordered to blow themselves up in crowded areas, but managed to escape and find help instead of detonating the bombs. Boko Haram – a Nigeria-based militant Islamist group whose name translates roughly to“‘Western education is forbidden” – expressly targets schools and has abducted more than 2,000 women and girls since 2014. Female suicide bombers are seen by the militants as a new weapon of war. In 2016, The New York Times reported at least one in every five suicide bombers deployed by Boko Haram over the previous two years had been a child, usually a girl. The group used 27 children in suicide attacks in the first quarter of 2017, compared to nine during the same period the previous year. (Photo by Adam Ferguson for The New York Times/World Press Photo)

Watch houses burn: A group of Rohingya at the Leda makeshift settlement in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh, watch as houses burn just across the border in Myanmar. September 9, 2017. After militants of the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) launched an assault on a Myanmar government police post in August, Rohingya villages were targeted and houses burned, causing an exodus of refugees to Bangladesh. The Myanmar government blamed ARSA for the village attacks. According to the refugees themselves and Human Rights Watch, which analyzed satellite imagery, Myanmar security forces set the fires. By the end of November more than 350 villages had been partially or completely destroyed. (Photo by Md Masfiqur Akhtar Sohan/NurPhoto Agency/World Press Photo)

Rohingya crisis: The bodies of Rohingya refugees are laid out after the boat in which they were attempting to flee Myanmar capsized about eight kilometers off Inani Beach, near Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh. Around 100 people were on the boat before it capsized. There were 17 survivors, September 28, 2017. The Rohingya are a predominantly Muslim minority group in Rakhine State, western Myanmar. They number around one million people, but laws passed in the 1980s effectively deprived them of Myanmar citizenship. Violence erupted in Myanmar on 25 August after a faction of Rohingya militants attacked police posts, killing 12 members of the Myanmar security forces. Myanmar authorities, in places supported by groups of Buddhists, launched a crackdown, attacking Rohingya villages and burning houses. According to the UNHCR, the number of Rohingya that subsequently fled Myanmar for Bangladesh reached 500,000 on Sept. 28. (Photo by Patrick Brown/Panos Pictures for Unicef/World Press Photo)

Not my verdict: John Thompson is embraced in St Anthony Village, Minnesota, USA, after speaking out at a memorial rally for his close friend Philando Castile, two days after police officer Jeronimo Yanez was acquitted of all charges in the shooting of Castile, June 18, 2017. In July 2016, Officer Yanez had pulled over Castile’s car in Falcon Heights Minnesota as it had a broken brake light. Castile, an African American man, handed over proof of insurance when asked, and informed the officer that he had a gun in the car. Police dashboard camera footage reveals that Yanez shouted, “Don’t pull it out,” and fired seven shots into the vehicle, fatally wounding Castile. Yanez was found not guilty of second degree manslaughter on 16 June 2017. Thompson was a high-profile presence at rallies following his friend’s death. (Photo by Richard Tsong-Taatarii/Star Tribune/World Press Photo)

A passerby comforts U.S. tourist Melissa Cochran, injured in an attack on pedestrians at Westminster Bridge in London, UK, March 22, 2017. Melissa survived, but lost her husband, Kurt, in the attack. On March 22, Khalid Masood drove a rented SUV along the sidewalk of Westminster Bridge, near the British Houses of Parliament in central London. Three people were killed instantly, and two more died in the days after the attack; at least 40 were injured. Armed with two knives, Masood left the car and attempted to enter the grounds of parliament, where he fatally stabbed one of the policemen who tried to stop him, before being shot and killed. Born Adrian Russell Elms in Kent, UK, Masood changed his name when he converted to Islam. Although ISIS claimed responsibility for the attack the following day, police investigating found no evidence of any links between Masood and either ISIS or al-Qaeda. (Photo by Toby Melville/Reuters/World Press Photo)

A huge crowd at the Kim Il Sung stadium awaits the start of the Pyongyang marathon. An official guards the exit in Pyongyang, North Korea, April 9, 2017. More than 50,000 spectators assembled to see the start of the marathon. Thousands more gathered on the streets of the North Korean capital along a route that took runners past such landmarks as the Arch of Triumph, Kim Il-sung Square and the Grand Theatre. North Korea is one of the most isolated and secretive nations on earth. A leadership cult has grown around the Kim dynasty, passing from Kim Il-sung (the Great Leader) to his son Kim Jong-il (the Dear Leader) and grandson, the current supreme leader Kim Jong-un. The country is run along rigidly state-controlled lines. Local media are strictly regulated, and the foreign press largely excluded, or, if allowed access closely accompanied by minders. (Photo by Roger Turesson/Dagens Nyheter/World Press Photo)

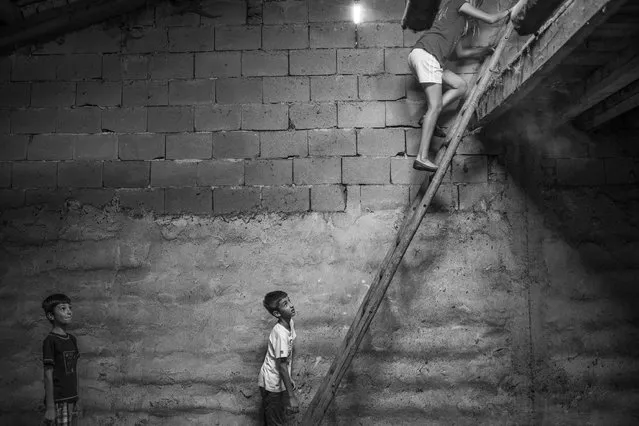

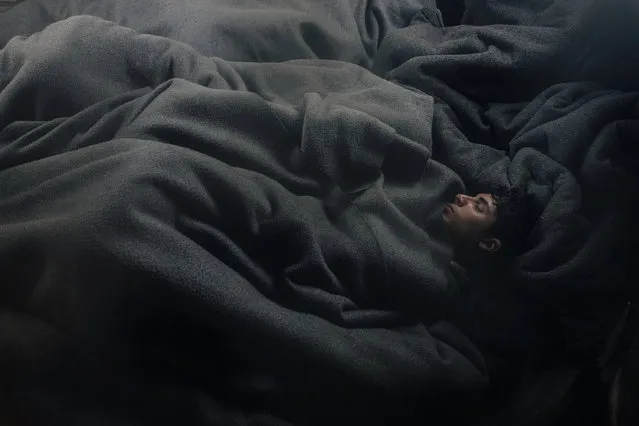

Lives In limbo: Young Afghans sleep in an abandoned train wagon in Belgrade, Serbia, January 12, 2017. The tightening of the so-called Balkan route into the European Union stranded thousands of refugees attempting to travel through Serbia to seek a new life in Europe. Many spent the freezing winter in derelict warehouses behind Belgrade's main train station. The UNHCR reported that the number of refugees in Serbia had increased from 2,000 in June 2016 to more than 7,000 by the end of the year. Some 85 percent were accommodated in government facilities, most of the others slept rough in the capital. (Photo by Francesco Pistilli/World Press Photo)

Girls: Alena (33) was born in Ukraine and raised in an orphanage. She moved from Donetsk to St Petersburg after the war in Ukraine, thinking that she was being offered work as an administrator in a brothel, only to find that the job was as a s*x worker, September 22, 2017. s*x workers pictured in their apartments, in St Petersburg, Russia. Official statistics say that there are one million s*x workers in Russia. Silver Rose, a St Petersburg NGO, puts that at closer to three million, with more than 50,000 women working in St Petersburg alone. Prostitution is illegal in Russia, and though fines are not large (about €28) women are vulnerable to extortion because they fear the consequences of having a criminal record. According to Silver Rose, despite the stereotypical view of s*x workers, only a small percentage have taken to prostitution because they are addicts or living in extreme poverty. The decline of the Russian economy has led to a growing number of women—many over the age of 35—who have lost jobs in such fields as business or education becoming s*x workers. (Photo by Tatiana Vinogradova/World Press Photo)

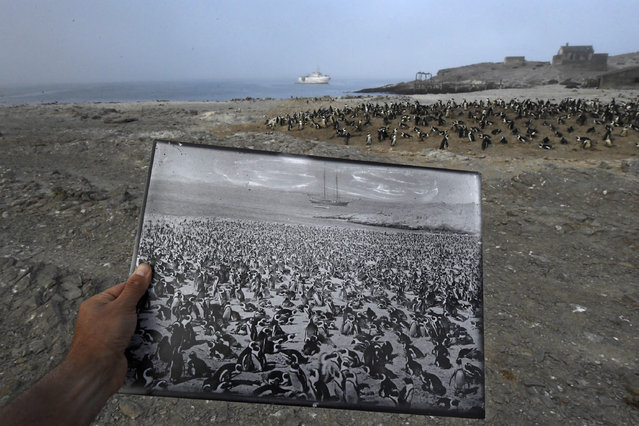

Back in time: A historic photograph of an African penguin colony, taken in the late 1890s, is a stark contrast to the declining numbers seen in 2017 in the same location, on Halifax Island, Namibia. The colony once numbered more than 100,000 penguins, March 11, 2017. The African penguin, once southern Africa’s most abundant seabird, is now listed as endangered. Overall, the African penguin population is just 2.5 percent of its level 80 years ago; research conducted on Halifax Island by the University of Cape Town indicates the population has more than halved in the past 30 years. Historically, the demand for guano (bird excrement used for fertilizer) was a cause of the decline: the birds burrow into deposits of guano to nest. Human consumption of eggs and overfishing of surrounding waters are also seen as causes. In the seas around Halifax Island sardine and anchovy – the chief prey of the African penguin – are now almost absent. (Photo by Thomas P. Peschak/World Press Photo)

Latidoamerica: The crime scene in the upscale Zona Viva hotel and nightlife district in Guatemala City, Guatemala, after 31-year-old Karina Marlene had been gunned down by six shots fired from a taxi, December 29, 2010. After years of experiencing social chaos, drugs trafficking and political corruption, many Latin Americans are determined to resist the violence afflicting their homelands. Armed conflict and socio-economic collapse in a number of Latin American countries in the latter part of the 20th century forcibly displaced hundreds of thousands of people, both to neighboring states and northwards to the US. Stricter US policies in the mid-1990s led to the deportation of members of maras, Hispanic gangs formed on the streets of cities such as Los Angeles, and fueled gang warfare across Latin America. This, and violence associated with both the drugs trade and the so-called War on Drugs, has led to a number of Latin American cities ranking with the most violent in the world outside of a conflict zone. This project describes the fear, anger and impotence of victims amidst the daily terror of street gangs, murder and thievery in Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala and Colombia. The photographer wanted to document the heart of uncontrolled violence in Latin America, and the social and political factors that aggressively reinforce that violence, as well as the determination to end it. (Photo by Javier Arcenillas/Luz/World Press Photo)

People scramble for shelter after gunshots ring out at the Route 91 country music festival in Las Vegas, Nev., October 1, 2017. Fifty-eight people were killed and more than 500 wounded when gunman Stephen Paddock opened fire on a crowd of around 22,000 concertgoers at the Route 91 Harvest Country Music Festival at the Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino in Las Vegas, Nev. Paddock fired for ten minutes from a suite on the 32nd floor of the hotel. Paddock killed himself in his hotel room after the shooting. Twenty-three guns were found in his room, some of which had been specially adapted to mimic fully automatic weapons, firing 400 to 800 rounds per minute. Paddock had no criminal record, and no motive was established for the massacre. (Photo by David Becker/Getty Images/World Press Photo)

Feeding China: Thousands of people converge on Xuyi County every summer for the annual crayfish eating festival, June 13, 2016. Rapidly rising incomes in China have led to a changing diet and increasing demand for meat, dairy and processed foods. China needs to make use of some 12 percent of the world’s arable land to feed nearly 19% of the global population. New technologies and agricultural reform offer a partial solution, but problems remain as farmers and the young flock to work in cities, leaving an aging rural population, and as land becomes contaminated by industry. (Photo by George Steinmetz for National Geographic/World Press Photo)

Jump: Rockhopper penguins live up to their name as they navigate the rugged coastline of Marion Island, a South African Antarctic Territory in the Indian Ocean, April 18, 2017. Among the most numerous of penguins, rockhoppers are nevertheless considered vulnerable, and their population is declining, probably as the result of a decreasing food supply. The birds spend five to six months at sea, coming to shore only to molt and breed. They are often found bounding, rather than waddling as other penguins do, and are capable of diving to depths of up to 100 meters in pursuit of fish, crustaceans, squid and krill. (Photo by Thomas P. Peschak/World Press Photo)

Suzanne, 11 years old. two months before that image was taken, she experienced breast ironing until her breasts were totally gone. November 2016, East Cameroon. (Photo by Heba Khamis/World Press Photo)

Dumpster diver: A bald eagle feasts on meat scraps in the garbage bins of a supermarket in Dutch Harbor, Alaska, February 14, 2017. Once close to extinction, the bald eagle has made a massive comeback after concerted conservation efforts. Unalaska has a population of around 5,000 people, and 500 eagles. Some 350 million kilograms of fish are landed in Dutch Harbor annually. The birds are attracted by the trawlers, but also feed on garbage and snatch grocery bags from the hands of unsuspecting pedestrians. Locally, the American national bird is known as the “Dutch Harbor pigeon”. (Photo by Corey Arnold/World Press Photo)

Djeneta (right) has been bedridden and unresponsive for two-and-a-half years, and her sister Ibadeta for more than six months, with uppgivenhetssyndrom (resignation syndrome), in Horndal, Sweden, March 2, 2017. Djeneta and Ibadeta are Roma refugees, from Kosovo. Resignation syndrome (RS) renders patients passive, immobile, mute, unable to eat and drink, incontinent and unresponsive to physical stimulus. It is a condition believed to exist only amongst refugees in Sweden. The causes are unclear, but most professionals agree that trauma is a primary contributor, alongside a reaction to stress and depression. It is also not clear why cases are found exclusively in Sweden. RS has so far affected only refugees aged seven to 19, and mainly those from ex-Soviet countries or the former Yugoslavia. For many, the syndrome is triggered by having a residence application rejected. Granting residence to families of sufferers is often cited as a cure. (Photo by Magnus Wennman/Aftonbladet/World Press Photo)

Warriors who once feared elephants: Mary Lengees, one of the first female keepers at the Reteti Elephant Sanctuary in northern Kenya, caresses Suyian, the sanctuary’s first resident, who was rescued in 2016, when she was just four weeks old, October 3, 2016. Women at Reteti are seen as bringing important nurturing skills into the workforce. Orphaned and abandoned elephant calves are rehabilitated and returned to the wild, at the community-owned Reteti Elephant Sanctuary in northern Kenya. The Reteti sanctuary is part of the Namunyak Wildlife Conservation Trust, located in the ancestral homeland of the Samburu people. The elephant orphanage was established in 2016 by local Samburus, and all the men working there are, or were at some time, Samburu warriors. In the past, local people weren’t much interested in saving elephants, which can be a threat to humans and their property, but now they are beginning to relate to the animals in a new way. Elephants feed on low brush and knock down small trees, promoting the growth of grasses – of advantage to the pastoralist Samburu. (Photo by Ami Vitale for National Geographic/World Press Photo)

Amazon – Paradise Threatened: Scarlet ibises fly above flooded lowlands, near Bom Amigo, Amapá, Brazilian Amazon, February 5, 2017. After declining from major peaks in 1995 and 2004, the rate of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon increased sharply in 2016, under pressure from logging, mining, agriculture and hydropower developments. The Amazon forest is one of Earth’s great “carbon sinks”, absorbing billions of tonnes of carbon dioxide each year and acting as a climate regulator. Without it, the world’s ability to lock up carbon would be reduced, compounding the effects of global warming. (Photo by Daniel Beltrá/World Press Photo)

Waiting for freedom: A young southern white rhinoceros, drugged and blindfolded, is about to be released into the wild in Okavango Delta, Botswana, after its relocation from South Africa for protection from poachers, September 21, 2017. Southern white rhinos are classified as “near threatened”. Rhinoceros horn is highly prized, especially in Vietnam and China, for its perceived medicinal properties, and in places is used as a recreational drug. Horns can fetch between €20,000 and €50,000 per kilogram. Poaching in South Africa rose from 13 rhinos a year in 2007 to a peak of 1,215 in 2014, and although these figures have declined slightly since then, losses are still unsustainable. Botswana is saving rhinos from poaching hotspots in South Africa and re-establishing populations in its own wildlife sanctuaries. (Photo by Neil Aldridge/World Press Photo)

Omo change: Indigenous Karo children play in the sand on the banks of the Omo River in Ethiopia. The Karo people are entirely dependent on the river for food: both for fish and crops grown in fertile flood soil. The forest seen in the background was cleared to make way for commercial cotton plantations, July 24, 2011. Ethiopia is in the midst of an economic boom, with growth averaging 10.5 percent a year – double the regional average. One of the areas most impacted by this is the Omo Valley, an area of extraordinary biodiversity along the course of the Omo River, which rises in the central Shewan highlands and empties into Lake Turkana, on the border with Kenya. Some 200,000 people of eight different ethnicities live in the Omo Valley, with another 300,000 around Lake Turkana in Kenya. Many are reliant on the river for their food security: on fish in the river and lake, and on crops and pastures grown in the fertile soil deposited by annual natural floods. Gibe III Dam – at 243 meters the tallest in Africa, and generating some 1,800 MW of hydroelectric power – was built with a dual aim: to provide energy for the booming economy and for export, and to deliver an irrigation complex for high-value agricultural development. It was also said that the dam would become a tourist attraction, of socio-economic benefit. Both Ethiopian and Kenyan governments support the dam and have disputed claims of a negative environmental impact, but critics point to such adverse effects as the cessation of natural floods, diminishing biodiversity, falling water levels in Lake Turkana, and the displacement of traditional peoples who have lived for centuries in a delicate balance with the environment. The photographer visited the Omo Valley during the final years of the dam’s construction, with the aim of producing a meditation on how important investments can nonetheless put the human-environment balance at risk, and on how the changes brought about by the presence of such large amounts of money disrupt existing equilibrium. (Photo by Fausto Podavini/World Press Photo)

The Boys and the bulls: Three 16-year-olds get ready to train with real bulls at a bull ranch in Albacete, Spain, where they have traveled especially for the experience, from Almería, 350 kilometers away, February 19, 2017. Bullfighting has long generated controversy and is declining in popularity, even in Spain, yet across the country boys still dream of stardom in the arena, and attend bullfighting schools to learn the requisite skills. At the Escuela Taurina Almería, a bullfighting school in Almería, Spain, boys aged 10 to 16 practice three times a week. The minimum age that boys may participate in a proper corrida, with a live bull, is 16. In February 2018, the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child urged Spain to ban children from attending bull fights or bullfighting schools. Proponents say that bullfighting is part of Spain’s national fabric, an art form that encourages striving for the best. (Photo by Nikolai Linares Larsen/World Press Photo)

Lagos Waterfronts under Threat: A boat with expats from Lagos Marina is steered through the canals of Makoko community – an ancient fishing village that has grown into an enormous informal settlement – on the shores of Lagos Lagoon, Lagos, Nigeria, February 24, 2017. Makoko has a population of around 150,000 people, many of whose families have been there for generations. But Lagos is growing rapidly, and ground to build on is in high demand. Prime real estate along the lagoon waterfront is scarce, and there are moves to demolish communities such as Makoko and build apartment blocks: accommodation for the wealthy. Because the government considers the communities to be informal settlements, people may be evicted without provision of more housing. Displacement from the waterfront also deprives them of their livelihoods. The government denies that the settlements have been inhabited for generations and has given various reasons for evictions, including saying that the communities are hideouts for criminals. Court rulings against the government in 2017 declared the evictions unconstitutional and that residents should be compensated and rehoused, but the issue remains unresolved. (Photo by Jesco Denzel/World Press Photo)

Marathon des sables: Participants set off on a timed stage of the Marathon des Sables, in the Sahara Desert in southern Morocco. The Marathon des Sables (Marathon of the Sands) is run over 250 kilometers in temperatures of up to 50℃. Participating runners and walkers must carry their own backpacks with food, sleeping gear, and other material. The marathon is conducted in six stages, over seven days, with one long stage of more than 80 kilometers. The first Marathon des Sables was held in 1986 with 186 competitors. The event now attracts more than 1,000 participants from around 50 countries. (Photo by Erik Sampers/World Press Photo)

Galapagos – Rocking the Cradle: Four major ocean currents converge along the Galapagos archipelago, creating the conditions for an extraordinary diversity of animal life, April 25, 2016. The islands are home to at least 7,000 flora and fauna species, of which 97 percent of the reptiles, 80 percent of the land birds, 50 percent of the insects and 30 percent of the plants are endemic. The local ecosystem is highly sensitive to the changes in temperature, rainfall and ocean currents that characterize the climatic events known as El Niño and La Niña. These changes cause marked fluctuations in weather and food availability. Many scientists expect the frequency of El Niño and La Niña to increase as a result of climate change, making the Galapagos a possible early-warning location for its effects. (Photo by Thomas P. Peschak for National Geographic/World Press Photo)

16 Apr 2018 00:01:00,

post received

0 comments