A flying handbag at a monastery in Xindu, China, April 1984. “This photo is an enigma. Even I can’t say for sure what’s happening. I didn’t know what I had taken at the time. It was only afterwards, when I developed the film, that I saw the handbag. It was April 1984 and I was on assignment in China, which was just opening up to foreigners. I had no particular commission, though: I could shoot whatever I wanted. On this day, I was visiting a monastery at Xindu in the Sichuan province. There was a symbol on the wall that meant “happiness”. The place was full of Chinese tourists and the tradition was to stand 20 metres from the sign, then walk towards it with eyes closed and try to touch the centre of the four raised points. As a photographer, I have always been interested in gestures – I was once described as someone who made arms dance. And now I found myself in front of this extraordinary ballet: a young man who has just touched the sign and a second, in a hat, approaching with his hand out. I remember the sensation of something moving, but I really don’t remember the handbag”. (Photo by Guy Le Querrec/Magnum Photos)

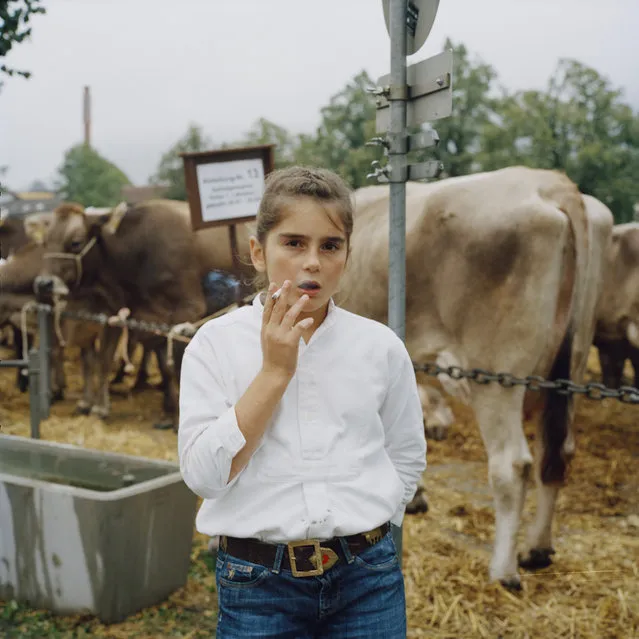

A girl smoking at a cattle show in Appenzell, Switzerland. “Appenzell is a beautiful and very odd place. It’s a tiny rural town in the east of Switzerland, built in the 16th century. Here, all the cliches are true: the fondue and the yodelling, the pink cows and the magnificent ski slopes. It’s also a place with very local habits. They still celebrate the new year according to the Julian calendar. And every October, they hold the Viehschau cattle show – a beauty show, but for cows. I first visited it in 2013. As soon as I started taking photographs, I noticed that many of the younger kids were passing around cigarettes, smoking one after another. They weren’t misbehaving; their parents were around and they all seemed comfortable with it. Letting your children smoke at the cattle show is a long-standing custom, I learnt. Kids as young as six do it. Appenzeller people are quite strong-minded. I have tried to ask why they let their children smoke, but no one has ever given me a clear explanation. I think most of the parents hope their kids will find it disgusting and won’t do it when they’re older. Or maybe they feel they should treat their children as equals on this special occasion. As far as I know, it only happens here, and only at that particular time of year. The adults grew up with the custom and now no one questions it”. (Photo by Jiří Makovec)

Inside a Glasgow shipyard. “In the 1990s I lived in Govan, on the south side of Glasgow, near the shipyard. I wanted to grab my own little slice of Glasgow history. These are the shipyards that helped build the city and make its industrial capabilities renowned the world over. There are three yards in Glasgow now. Two are owned by BAE Systems and dedicated to defence. I haven’t tried to get in, but I’ve been told it’s pretty much impossible. The third yard, Ferguson Marine, nearly went into liquidation in 2014. I was 24 and wanted to get into the yards before that world disappeared. I remember being impressed by the monumental scale of it all. Parts of the ship seem quite organic: the blades of the propeller look like the underside of a whale. I shot it on an old Nikon in black and white, as that puts the focus on shapes and sizes. People have asked me if it’s perspective that makes the workers look so tiny. But it’s not. They are to scale”. (Photo by Jeremy Sutton-Hibbert)

The whales at Thorntonloch, Scotland in 1950. “I was 11 when I went to see the whales stranded on Thorntonloch beach. There were 147 pilot whales, the largest beaching in Scotland, and no one had any idea why they were there. There was a sea of whales stretched along the sand. Some were clearly dead, but many were still alive. When the larger whales, which were more than 20ft long, flapped their tails, people jumped. I was amazed: I’d never seen a whale before, only pictures in a book; there was no television in Scotland until 1952. The scene was like something you might see at the cinema. If you look closely, everyone is well dressed: men and women would not go out casually dressed as we do today. I remember seeing people in uniform – the Scottish Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animal – who were killing the whales with a crude bolt gun usually used to slaughter cows. I stood next to them as they put the guns to the whales’ heads, then there was a boom. Some were also shot with rifles. Cranes loaded carcasses on to lorries; others were hauled up manually, using ropes. The whales were transported to slaughterhouses all over Scotland and as far south as Cheshire. There was a real sense of sadness; everyone was very serious, and respectful of the whales, as you can see in the picture. When I look back, I can see the whales stretched out along the beach as if it were yesterday. Something like that never leaves you”. (Photo by Sandy Darling/Bulletin and Scots Pictorial)

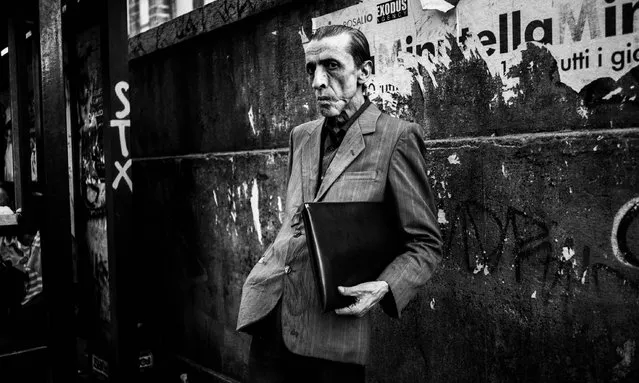

The haunted face of Sicily. “I’d just come back from shooting in a poor district of Palermo. I was waiting for the bus and I saw this guy. His face was a battlefield. The dark energy was all there. He’s not a mafioso. Mafiosi have a totally different body language. They stand tall, they are aggressive. I just saw this battered, haunted face of Sicily. I work with a Hasselblad 500cm so I hold the camera at waist level and look down into the viewfinder. I composed, judged the focus, aperture and shutter speed, then I shot – two or three frames. He looked straight at me. He was frozen somehow. He didn’t realise I was taking his picture. Immediately after, I approached him and asked if I could take a closer one. He said: “No, no, no, no, no!” I asked why. His voice was anxious. “Because I’m nervous!” Why are you nervous? “Because I’m waiting for the bus!”. (Photo by Mimi Mollica)

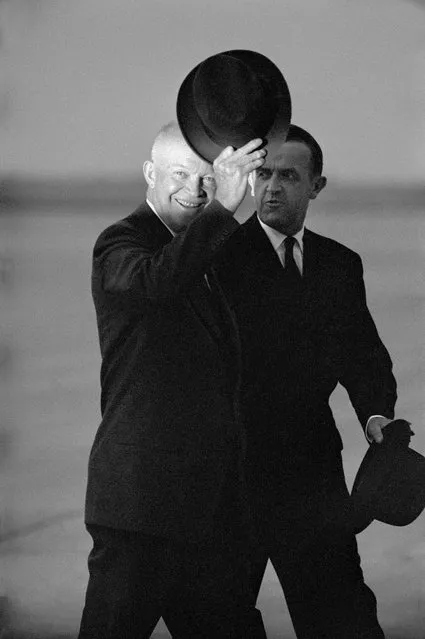

Dwight Eisenhower, left, with Swiss president Max Petitpierre at the 1955 Geneva summit. “In the 1930s, as Hitler rose to power, I left Austria for Israel. I started earning a living on the beaches of Netanya, near Tel Aviv, taking pictures of young mothers sitting on the beach with their children. I also worked as a kindergarten photographer and a taxi driver. I didn’t have any ambition – it was nice simply taking pictures of families. But the second world war changed my life. I spent most of it in the Western Desert, moving heavy machinery in a depot near Haifa, and selling cameras to the soldiers from the Middlesex Battalion. My family, who stayed in Vienna, all died in the gas chambers. When I returned to Vienna at the end of 1946, it was a shambles. Now I wanted to show what life was like in the aftermath of the war. In 1955, there was talk about a four-power conference where the big players – the Soviet Union, the US, Britain and France – would discuss how to make a long-lasting peace. The mood was uplifting, full of hope. For the first time in the history of diplomacy, the Big Four were sitting together and talking – and the future of the civilised world depended on it. About 30 photographers were at the airport in Geneva, where the conference was held, all waiting for the American President Dwight Eisenhower to arrive and be greeted by Max Petitpierre, the Swiss president. Most of the photographers had flashes and some had newfangled devices where the film was wound on by a motor. I had my Leica and that was all. I looked at them all and thought: “There is usually some hitch – when their film is being moved along, that will be when there’s an interesting picture to be taken”. And that is exactly what happened. A beam of light caught Eisenhower, leaving Petitpierre in the shadow. It seems as if I was the only photographer that day who got the picture just right: in other people’s shots, the light was on Eisenhower’s stomach, or his hat was obscuring his face. After the conference came the Austrian state treaty, granting the country independence. Then in 1956, the Hungarian revolution happened – but it was put down by the Soviets, and the west did nothing. I realised that, although reportage pictures have the power to move the world, they do not have the power to change it”. (Photo by Erich Lessing/Courtesy Magnum Photos)

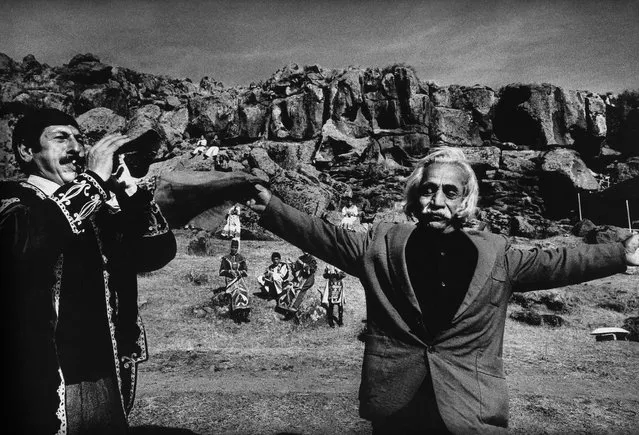

An Armenian man dances for his lost son in the mountains near Aparan, Armenia, 1998. “In 1998, I found myself in Aparan, a large town an hour’s drive from Armenia’s capital, Yerevan. A local dance troupe was performing that evening, in the open air, with most of the suburb in attendance. As soon as I took my first shot, an old man approached me. Tears streamed down his face. He told me that his son had died. That he had been electrocuted, that he was his pride and joy, and that I looked just like him. He broke into sobs and moved towards me with outstretched arms. His name was Ishran. I asked if he would dance for me, and he began dancing. The troupe paused and perched on an outcrop of rocks in the background. It was beautiful, not because the man is beautiful, but because he represents something deep inside the collective consciousness of the Armenian community: a celebratory resilience in the face of overwhelming loss”. (Photo by Antoine Agoudjian)

A love story with two log choppers. “In 1993, I was working on a project about life in the Olomouc region of Czechoslovakia. One day, I came to the village of Dlouhá Loučka-Křivá and went into a courtyard where I saw two old people, a husband and wife, sawing firewood for winter. They were working quietly, concentrating. I watched them fetch a beam from a wrecked barn, but they didn’t discuss how they planned to carry it to the saw. The woman faced one way, the man the other. When they realised, the woman eventually turned and followed her husband. The picture I took is the picture of many relationships – when each partner wants something different, but they have to come to an agreement, pull together eventually”. (Photo by Jindrich Streit)

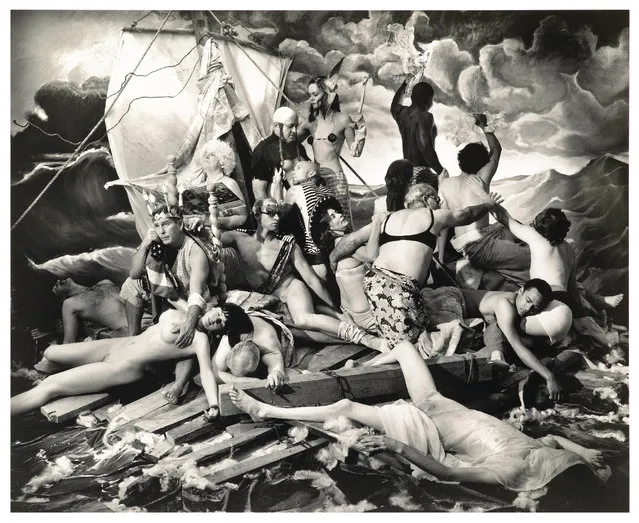

“Anyone who is a Republican has a spiritual problem” … The Raft of George W. Bush, NM, 2006. “This was based on Théodore Géricault’s painting The Raft of the Medusa, which recorded a great tragedy in French history. Géricault depicted the aftermath of a terrible act of cowardice by the Medusa’s captain and his officers. They ran the ship aground off the coast of what is now Mauritania in 1816. When they couldn’t set the frigate free, they took all of the small boats and left more than 140 passengers to fend for themselves on a raft. Only 15 survived, having resorted to cannibalism. When I saw the painting in the Louvre, I noticed a correlation between that tragedy and the eight years of George W. Bush’s administration. I think Bush would have been a wonderful president of the Baseball Association. But he had no talent for the job of president of my country. I spent a long time looking at the original painting, but decided to add something: a crown of lights on Bush’s head, to represent his little thoughts. And I had his hand fondling the breast of someone who I thought might be Condoleezza Rice, his secretary of state”. (Photo by Joel-Peter Witkin)

A girl and her maid on a “Europeans only” bench in Johannesburg, 1956. Working as a black photographer in apartheid South Africa was not easy. You had to always know where you were and who was around you. If the police were there, you couldn’t take photos – and the police were always there. If it was difficult for me to get a shot openly, I’d have to improvise: hide my camera in a loaf of bread, a half-pint of milk, even a Bible. When I got back to the office, I had to have a picture with me no matter what. My editors at the Rand Daily Mail would not take any nonsense. But that was fine – they wanted the pictures and I wanted to become one of the greats. I did not want to leave the country to find another life. I was going to stay and fight with my camera as my gun. I did not want to kill anyone, though. I wanted to kill apartheid. My editors always pushed me. “Work as hard as you can”, they’d say, “to defeat this animal apartheid. Show the world what is happening”. I never staged pictures. They were moments I came across. I took this in 1956, while driving through a wealthy suburb in Johannesburg. I saw the girl on the bench and stopped. The woman worked for her parents, most likely a rich local family. These labels – “Europeans only”, “Coloureds only” – were on everything, by order of the government. When I saw Europeans only, I knew I would have to approach with caution. But I didn’t have a long lens, just my 35mm, so I had to get close. I did not interact with the woman or the child, though. I never ask permission when taking photos. I have worked amid massacres, with hundreds of people being killed around me, and you can’t ask for permission. I apologise afterwards, if someone feels insulted, but I want the picture. I took about five shots and went straight back to the office. I processed it, then showed it to the editor and he said it was wonderful. It was published worldwide: for a lot of countries, apartheid was the news of the day. Ever since, I have been trying to find the woman and child. I have no leads, but I would love to say: “Thank you very much, for not interfering with me when I took this”. (Photo by Peter Magubane)

Woman on a mountainside outside Tehran. “A lot of the photo albums in Iran from 20 or 30 years ago have the same stock landscape shot on the front: a green and flowery mountainside, beautiful and hopeful. I wanted to find my own homage to the stock mountain photograph, so I located this dry, abandoned mountain in Tehran. It’s the polar opposite: desolate, flowerless, almost hopeless. I chose nine people, people who I thought represented my generation, and took them to the mountain to find the one spot that really called to them. Somayyeh chose this tree. I’ve known Somayyeh for eight years. She is from a very conservative part of the country, just outside Isfahan. For years, she lived in this town with her family and dreamed of going to Tehran. When she did, the city changed her: she wasn’t able to be invisible in her home town, but in Tehran she found anonymity and she divorced her husband. Somayyeh is fighting every day to find a space for herself in the world – I really admire her”. (Photo by Newsha Tavakolian)

04 Aug 2016 12:34:00,

post received

0 comments